William S. Rosecrans

Braxton Bragg

Strength:

Union: 43,400

Confederate: 37,712

Casualties:

Union: 13,249 (1,730 killed, 7,802 wounded, 3,717 captured/missing)

Confederates: 10,266 (1,294 killed, 7,945 wounded, 1,027 captured/missing)

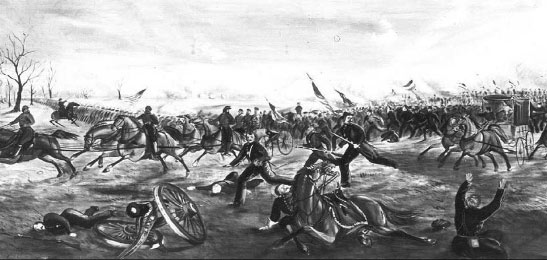

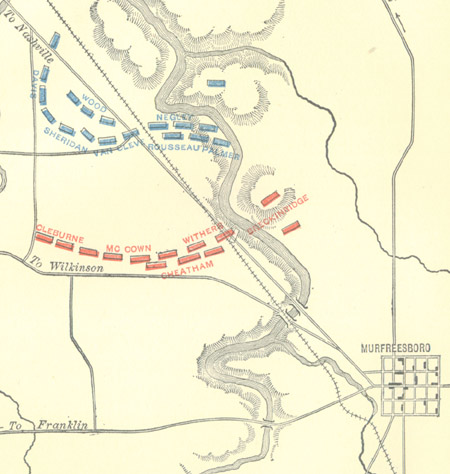

We return to the battle December 31, 1862 and the Union right flank has been smashed by Hardee sending McCook’s men back against the Nashville Turnpike. There they regrouped, with their backs to the wall.

In the center things were not going much better, we pick up Fiske’s narrative there:

The Confederate center, hitherto silent, opened a heavy fire upon Sheridan and Negley, while their victorious left hurled upon Sheridan, whose defeat would now complete the destruction of the Union right. But in young Philip Sheridan the advancing rebels encountered an officer of very different mettle from those they had disposed of that morning. When he found his flank uncovered by McCook’s retreat, he withdrew his right and ordered his left to push back the enemy at point of bayonet; and while this charge, superbly conducted by Colonel Roberts, drove off the enemy in disorder, he used the precious moments in forming a new front at right angles to his old one and facing southward. In this new position he met the returning shock of rebel infantry, and held them at bay for two hours…

Maddened by this obstinate resistance, Bragg massed the entire left and center of his army against these two divisions, but was thrice driven back with frightful slaughter. At length, with his cartridge-boxes empty, his brigade commanders all killed, and 1800 men laid low, the noble Sheridan sat that he must retreat. One more desperate charge with cold steel, and before the enemy had recovered he withdrew his men to the rolling plain west of Nashville road where the new line of battle was forming. “Here we are,” he cried, as he met Rosecrans galloping up, “here we are, all that are left of us.” His magnificent resistance had saved the day.

(After several more hours of severe fighting the battle dissipated as darkness fell. That night Rosecrans held a war council and was advised by several generals to retreat to Nashville, but he demurred. Meanwhile, Bragg believed that he had won a great victory.)

When he [Bragg] got up on New Year’s Day and found the Union army was still in position, it was a great disappointment. Little was done that day. Brag spent it in reconnoitering to ascertain if his adversary was still present in full force. Rosecrans prepared to resume the offensive, and accordingly sent Van Cleve’s division with one of Palmer’s brigades to sieve the heights upon the east side of the river and plant batteries there, according to his original plan. This movement which threatened the town of Murfreesboro and Bragg’s communications, was unopposed and apparently not discovered until the next day. The batteries enfiladed the whole of Polk’s line, and it was necessary for Bragg either to storm the position or take his army away. On the afternoon of January 2, Breckinridge was sent back to the east side of the river and entrusted with the attack. At first Breckinridge was successful against Van Cleve; but Negley’s division coming to the rescue, led by Colonel John Miller, its senior brigade-commander, the Confederates were presently overpowered. Their line was exposed to the ranking fire of 58 guns from the Union batteries west of the river, and after an hour Breckinridge retreated, leaving 1700 men of his division killed and wounded.

(By the next day Bragg retreated to Shelbyville and Tullahoma in disgrace having failed to take his initial success and turn it into victory.)

Scanned from: John Fiske, The Mississippi Valley in the Civil War, (Cambridge: The Riverside Press,1900), 161-167