The Battle of Stone’s River (Murfreesboro), Tenn.

Rosecrans was at Nashville, where his first care was to repair the railway connecting him with his base of supplies at Louisville. Bragg had concentrated his forces at Murfreesboro whence he sent the indefatigable Morgan on excursions to tear up rails and break down bridges in Rosecrans’s rear; and for want of sufficient cavalry, Rosecrans like Buell found it hard to cheek these performances. The longer he stayed quiet, the worse the nuisance was sure to become ; and after due preparation he marched out of Nashville on the day after Christmas, to attack and overwhelm the enemy.

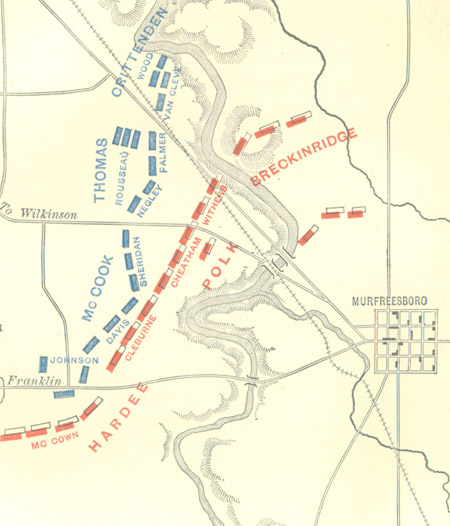

The town of Murfreesboro is a station on the Nashville and Chattanooga railroad, thirty miles southeast from Nashville. A mile to westward of the town the road to Franklin crosses Stone river, a sluggish tributary of the Cumberland. The sinuous river, and the railroad and turnpike straight as arrows, all run northwesterly and near together, through dense cedar-brakes interspersed with occasional clearings. It was this triple line of turnpike, railroad, and stream that was now to be made the scene of some of the most obstinate fighting of modern times. Bragg’s army was drawn up in line of battle at an acute angle with the river and mostly to the west of it. The left Wing under Hardee and the center under Polk were west of the river, and on the further side, to ward off any flank movement upon the town of Murfreesboro, was the right wing, composed of Breckenridge’s division of Hardee’s corps separated from its fellows. The general direction of the line west of the river was nearly north and south, with the left wing advanced southwestward. On the east side of Breckinridge’s division was considerably refused to the northeast. Such was the Confederate line of battle, – an arrangement apparently faultless and fully adequate to the work which Bragg had planned.

The Union army was drawn up to the westward of the river in a line somewhat zigzag, but for the most part parallel to the enemy’s front. The right wing under McCook stretched from the Franklin road to the Wilkinson turnpike. It consisted of three divisions, – first Johnson’s, resting on the Franklin road with its right refused in a crotchet, and then Davis’s; the third, which connected with the center at the Wilkinson pike, was commanded by a young officer named Philip Sheridan, who had lately won his first laurels at Perryville. The center, commanded by Thomas, consisted of two divisions, Negley’s and Rousseau’s, but in the plan of battle Palmer’s division of the left wing practically formed part of the center. Negley and Palmer were drawn up in line between Wilkinson and Nashville pikes, with Rousseau stationed in the rear as a reserve. The remainder of the left wing under Crittenden, consisting of Wood’s and Van Cleve’s divisions, reached from the Nashville pike across the railroad and rested its left on a bend in the river. Each line of battle, Union and Confederate, was about three miles in length, and each contained in infantry and artillery about 40,000 men.

It was well said by Frederick of Prussia that more than half the secret of winning battles lies in knowing how to take position. Rosecrans’s arrangement was well adapted to his purpose save in one quarter of the field, but the defect in that was a grave one. His plan to throw the two divisions of Wood and Van Cleve across the easily fordable river and crush the single division of Breckinridge. At that point is a commanding ridge upon which Union artillery, once posted, would enfilade the whole Confederate line. With the aid of this galling fire it seemed certain that Thomas, with his tow divisions and Palmer’s, would defeat the Confederate center; while the Union left, continuing its turning movement, would pass through Murfreesboro and occupy the Franklin road, thus cutting off the enemy’ retreat. In other words, the Union army, pivoting upon its right, was to be swung around in a semicircle, enveloping and destroying the enemy. It was for this purpose that Rosecrans massed his troops so heavily on his left.

If the pivot were to be shaken out of place, the whole turning movement would be spoiled and the army thrown upon the defensive.

[As it turns out] Bragg’s plan of battle was almost precisely the same as that of Rosecrans. With his left somewhat heavily massed and thrown forward, he intended to overlap and crush the Federal right. Swinging around his whole force west of the river with Polk’s right as its pivot, he would come in upon the Federal rear, fold the army back against the river, and, seizing the Nashville turnpike, cut of their retreat.

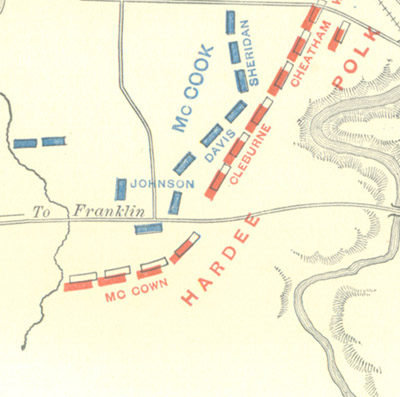

Under these circumstances it was imperatively necessary for Rosecrans to use extraordinary diligence in placing his right wing. This he can hardly be said to have done, and the error which he failed to rectify spoiled his plan of battle and came within an ace of destroying the Union army. The error was that McCook’s line was too long and thin and faced too much to the east, thus coming too near the enemy.

On the eve of the battle General Sheridan, accompanied by one of his brigade-commanders, General Sill, visited McCook’s headquarters and earnestly assured him that the arrangement was liable to invite disaster. But McCook di not profit by the warning.

Upon this scene of gross negligence fell the sudden shock of two Confederate divisions, one of which was led by Patrick Cleburne, the ablest division-commander in all the Confederate army west of the Alleghenies. The Confederate attack was superb and irresistible. The men rushed forward like an overwhelming torrent, and in a few minutes Johnson’s whole division was swept from the field in wild disorder toward the Wilkinson road. This catastrophe uncovered the right of Davis’s division, and upon this the victorious Confederates charged in heavy masses…

To be continued…

Scanned from: John Fiske, The Mississippi Valley in the Civil War, (Cambridge: The Riverside Press,1900), 161-167