The assault on Fort Blakely was the last significant battle of the Civil War and that in and of itself makes it an important historical event. However, there is a subplot to the battle that perhaps takes on an even greater importance. Involved in the assault were 5,500 Negro soldiers, the largest such gather at any one time in the Western theater. Not only was it the largest, it was not made up of freedmen, but ex-slaves. These soldiers were brought along not as laborers, but as fighters. Additionally, there were reports of atrocities being committed by the black troops once they entered the fort. One who witnessed the event wrote that the Negroes could not contain their enthusiasm once inside the fort as it “was unbound,” he said, “and they manifested their joy in every conceivable manner.” Yet another white soldier noted that the blacks did not “take a man” and killed all they captured.

Though exaggerations, to be sure, it is interesting that not a lot has been written about this important event and what happened during the confused and volatile minutes after the Fort was taken.

For example, in Joseph Glatthaar’s study of Negro involvement in the Civil War, “Forged in Battle”, he offered only a brief reflection of the racial elements involved. Glatthaar noted pithily that the Negroes “charged without orders” and that after getting inside the fort they acted “similarly” to Nathan B. Forrest’s men at Fort Pillow. (An excellent article about the racial issue at Fort Blakely by Michael W. Fitzgerald titled “Another Kind of Glory: Black Participation and its Consequences in the Campaign for Confederate Mobile,” in the Alabama Review (Oct 2001) must be mentioned as my inspiration to write this. I quoted from it in my book and my treatment of this battle.) Historians have thus far either treated the racial elements involved at Fort Blakely with kid gloves, or have virtually ignored it.

—-

Brig. Gen. John P. Hawkins commanded the Negro division of 5,500 strong. The column consisted of 3 brigades and 9 regiments as follows:

Brig. Gen. William A. Pile commanded First Brigade, made up of the Seventy-third, Eighty-second, and Eighty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry. Col. Hiram Scofield was in charge of Second Brigade, consisting of the Forty-seventh, Fiftieth, and Fifty-first U.S. Colored Infantry. Finally, Col. Charles W. Drew led the Third Brigade and its three units, the Seventy-sixth, Forty-eighth, and Eighty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry.

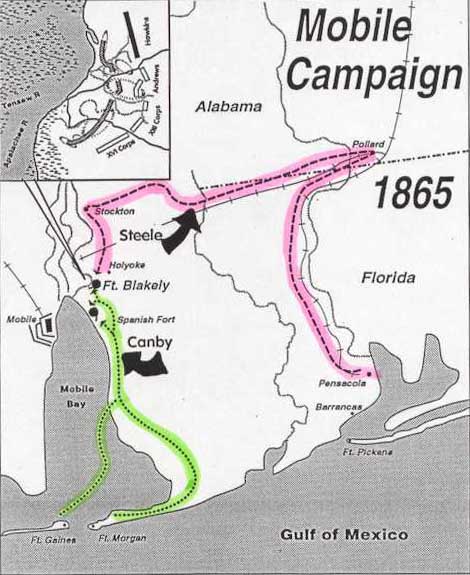

Hawkin’s division was part of Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele’s “Pensacola Column.” As Canby ascended up Fish River into the underbelly of Spanish Fort, Steele’s column had a rough time of it marching from Pensacola to Pollard, Stockton, and then south into Fort Blakely.

The trek was arduous as they faced torrential rain, quicksand, mud, and had to build miles of corduroy roads. “ The heavy rain… rendered the roads almost impassable,” wrote Steele afterwards.

Steele’s multi-racial column throughout the campaign faced the harshest conditions.

Canby took the Thirteenth and Sixteenth corps up the Fish River and invested Spanish Fort. The 11th Wisconsin was among them. Steele headed toward Pollard as a faint to confuse the defenders of Mobile as to his real objective, Fort Blakely.

As Steele left Pollard it was reported that his Negro soldiers “devastated the country, burning houses and stripping the people, women and children, of every means of subsistence.” And if this was not enough to elicit response, it was recorded that the soldiers “often ravished the women.” All of these claims had the desired effect. Upon hearing of the arrival of Steele’s troops, Confederate General St. John Liddell made it known that any Negro soldier captured would be sentenced to death.

It is highly doubtful that the Negro soldiers in Steele’s column behaved in the manner described above. Union generals kept close tabs on the Negros and gave specific orders that were “very strict” in regards to the black soldiers. Foraging was not allowed, and their behavior, by most accounts, was exemplary.

By the time Steele invested Fort Blakely on April 3, 1865, tensions within the fort were high. Before his men knew of Steele’s arrival, Liddell informed them that the enemy they were about to face was “composed principally of negroes,” former slaves. He then stressed the “importance of holding their position to the last, and with the determination never to surrender.” The implication was clear.

As the Negro troops dug in and began to envelop their pray, it was noted that they were “burning with an impulse to do honor to their race.”

The stage was set for not just the last significant land battle of the Civil War, but one with significant racial dimensions that were perhaps not equaled at any other time during the war.

Up next, Part III