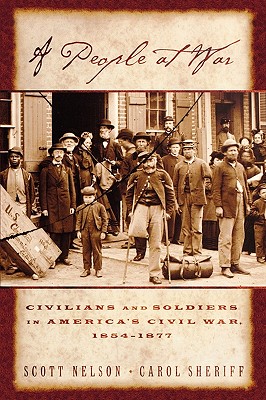

A People at War

A People at War

Civilians and Soldiers in America’s Civil War

Carol Sheriff and Scott Reynolds Nelson

384 pages; Paperback

Editorial Review - Library Journal vol. 132

In a crowded field of books on the Civil War era, Nelson (Steel Drivin’ Man ) and Sheriff (The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817–1862 ), historians at the College of William and Mary, give us something new—an engaging, informed portrait of two peoples at war, with an emphasis on how common soldiers and noncombatants adjusted to and were changed by the war. The authors spend more time in recruiting halls, military camps, hospitals, and prisons than in battle to observe what moved men to war and some to flee it, as well as how the physical and emotional demands of living away from home affected their sense of self and their national identity. At the same time, they discuss how the war came home to civilians, with the raids of armies and partisans, the demands of mobilization, the death and dismemberment of soldiers, the erosion of slavery, and the promise of freedom. They are especially good at linking the experience of, and expectations about, the war with Americans’ ambitions and interests in the West. Their vivid descriptions of disease and destruction will remind readers that war was hell even as it was also an instrument of social change. The new social historians’ interest in “the people” gets its full due in this readable, reliable, and remarkably relevant book. Highly recommended for university and large public libraries.—Randall M. Miller, Saint Joseph’s Univ., Philadelphia

When the Missouri Compromise was signed in 1820, the distance of railroads in the United States did not even equal a mile.[p.31] A telling piece of data that jumped out at me while reading Scott Reynolds Nelson and Carol Sheriff’s A People at War: Civilians and Soldiers in America’s Civil War, 1854-1877, and more specifically their chapter “The Road to Bleeding Kansas.” [A chapter I plan on handing out to my AP Students as a supplemental reading.]

The western expansion of the United States is something that has to be presented in detail as a causation (one of several) of the Civil War. The railroad explosion after 1820, though mainly impacting the North, opened up Western United States and caused the expansion of not just the population and economy but of the legal organization of the new territories into states. These new states placed pressure on a growing desire by some in the North to limit slavery’s expansion and some in the South to expand. As the country expanded, so too did the differences between too societies and their view of slavery as an institution of labor.

When looking at the factors that led to the outbreak of war, the caricature of a “Industrial North” and a “Slave South” as a main cause of the war, does “not hold up” as the authors note. [p.11] And I do agree that it is too simplistic to simply say that “slavery” caused the Civil War. Of course, as a general and significant cause, it was indeed the driving force. No slavery, no internal conflict over expansion, tariffs, ect. No threats and eventual declarations of secession. But that declaration does not help us understand the Civil War and the series of events that led up to that main event.

Nelson and Sheriff present what really feels like as a series of essays dealing with various aspects of the Civil War but all related to the theme of “a people at war.” The book goes to ground level and presents views from such aspects of the “people” including blacks and women. Social history is nothing new, and as the authors recognized, the publishing of American Civil War books has led to the extinction of many trees. So, to answer the authors in their Introduction, I would say their book is a nice addition to scholarship, though in the end it didn’t feel like anything special.

Nonetheless, the book is broken up nicely into both chronological and thematic aspects taking the narrative from the causes of war to Reconstruction, and I find it very useful as a teacher.

-Chris