Historian Ray Raphael has a very interesting article in the recent issue of American History Magazine. He argues that the tea party is filled with “myths” that have carried on to our present day. I though it fit to post it here since we have a modern “tea party” movement. Furthermore, I admit that I was, until now, one of those Americans who had always believed that the event was seen as a patriotic event by the Founding Fathers. But as Raphael states:

Historian Ray Raphael has a very interesting article in the recent issue of American History Magazine. He argues that the tea party is filled with “myths” that have carried on to our present day. I though it fit to post it here since we have a modern “tea party” movement. Furthermore, I admit that I was, until now, one of those Americans who had always believed that the event was seen as a patriotic event by the Founding Fathers. But as Raphael states:

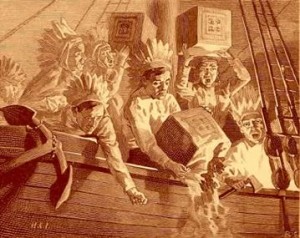

Revolutionary-era Americans, though, didn’t celebrate the event. This might seem strange, since the patriots were the celebrating sort. They staged festive ceremonies to commemorate anniversaries—the first Stamp Act protest, the act’s repeal, the Boston Massacre, the Declaration of Independence—but the “action against tea” or the “destruction of the tea” (as they variously called it) went unheralded in public ritual. For a half century, Americans shunned the tale, and certainly did not call it a tea party. At first, they didn’t dare. Anyone who had anything to do with the event could face prosecution, or at least a lawsuit. Privately, some people knew who was behind those Indian disguises, but publicly, nobody said a word. Moreover, many patriots viewed the destruction of tea as an act of vandalism that put the Revolution in a bad light. Patriots also downplayed the tea action because of its devastating impact. That single act precipitated harsh retaliation from the British, which in turn led to a long and ugly war.

The Boston Tea Party is now an iconic event suffused with myth, but below the surface is the story of a true act of revolution, carried out in a context of power politics, with surprising parallels in the modern era.

His three myths about the event are:

- The dispute was about higher taxes.

- Tea taxes were an onerous burden on ordinary Americans.

- Dumping British tea unified the patriots.

Do you agree or disagree with Raphael’s argument?

My first question to Mr. Raphael’s argument is who said those were the three main myths? I agree that the act itself did not represent a protest against taxes, but instead as a warning to the British. Samuel Adams (along with John Hancock), public enemy number 1 (and 2) as far as the British were concerned, did not take part in the event. This is symbolic as he loved to lead protests of any kind. The Tea Party concerned many Bostonians including Adams as one of the early tenets of these protesters was “property rights” which essentially included taxes against them. I think Raphael sets up a straw man that he could effectively knock down in an attempt to take a jab at today’s “Tea Partiers.”

Ira Stoll’s book gives the background of the Tea Party and Sam Adams’ reaction to it. Bostonians were boycotting tea and refusing to let ships dock that were carrying tea. The British persisted and the Tea Party happened in response.

Although no one was injured in the fracas, Adams did not condone the act.

I think you’re right on, the agenda behind this is to besmirch the modern day movement that has borrowed the name.

I agree with both of you. I think Chris pretty much sounded off my own thoughts. In my undergraduate work I took a course on social history of the U.S. We had to read one of Raphael’s books. Needless to say, I didn’t agree with much in that book either.

I get the need in history to study from the “bottom up,” and some books have really helped in the field of history. But historians like Raphael, and John Demos is another, sometimes take things too far. They only wish to be “cutting edge” or to use history for political means, as is the case here.

Pingback: Connectivism and Technology | Ken's Thoughts on Education and Technology