The idea of progress in American society and history is as old, perhaps, as the founding of this great country. In the study of American history the idea of progress has played a key role in the evolution of historical scholarship. This paper will seek to address two issues: first, how the nature of the meaning of progress changed from 1870 to 1920; second, how that change had both positive and negative consequences. This paper will address these issues while also providing a basic historical context of the evolution of the American historical profession.

The idea of progress in American society and history is as old, perhaps, as the founding of this great country. In the study of American history the idea of progress has played a key role in the evolution of historical scholarship. This paper will seek to address two issues: first, how the nature of the meaning of progress changed from 1870 to 1920; second, how that change had both positive and negative consequences. This paper will address these issues while also providing a basic historical context of the evolution of the American historical profession.

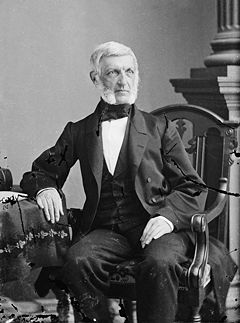

In 1854 historian George Bancroft spoke before the New York Historical Society and delivered an address titled, “The necessity, the reality, and promise of progress in the human race.” During the speech Bancroft outlined his philosophical belief in not just human progress, but historical progress towards a more virtuous existence as Americans. But there was a deeper meaning and one that hinged on progress towards an empire of liberty as established by the founding the nation, and with it the goal of a more perfect union. Bancroft’s view of progress was not secular, but spiritual and endowed by deep Christian values as established by the Founders:

The necessity of the progress of the race follows, therefore, from the fact, that the great Author of all life has left truth in its immutability to be observed, and has endowed man with the power of observation and generalization. Precisely the same conclusions will appear, if we contemplate society from the point of view of the unity of the universe. The unchanging character of law is the only basis on which continuous action can rest. Without it man would be but as the traveler over endless morasses ; the builder on quick-sands ; the mariner without compass or rudder, driven successively whithersoever changing winds may blow. The universe is the reflex and image of its Creator.

Bancroft believed in a “visible God” in history and the historian as the “poet” of history and of virtue. The historian was a moralizer who put history within a Christian context and explained important historical events as the “will of God.” Bancroft also saw the United States, though still a fledgling republic, as a world leader and an empire of liberty. For Bancroft the axis of history hinged on the struggle of good versus evil and America was a beacon for others to follow.

Bancroft was among the first generation of American Historians to study in Germany and adopt the German romantic and literate style of historical scholarship. While at the University of Gottingen, Bancroft studied under not just historians but theologians and philosophers as well. From his experiences in Germany Bancroft developed his Calvinistic and anti-Enlightenment approach to history that emphasized predetermination and God’s Will. Though never an abolitionist, when the Civil War was won Bancroft determined that the victory was preordained by God and that the American Republic had survived its greatest challenge and reached its “millennium.” He had boldly proclaimed the end of history for Americans.

The bestselling books at this time dealt with larger than life figures: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and they dealt with reverence the glorious American Revolution. Bancroft wrote a gigantic ten volume History of the United States from Discovery of the American Continent (1492-1660). The study started with colonization and was to proceed all the way to modern times, but he was never able to finish it. Bancroft was a prolific writer; the total number of words exceeded 1.7 million in his history of the United States alone.

Bancroft was guilty of aligning his facts within his theological approach to history and as a result his accuracy and interpretation was often deeply flawed. But his books were widely read and were themselves much anticipated historical events. Bancroft reflected the Victorian sensibility of Americans that the 19th Century demanded. However, by the time of his death in 1891 his patrician style of historical scholarship had been widely replaced with a more pragmatic and scientific approach.

By the late 19th Century the romantic and theological approach to history of Bancroft and his generation (Bancroft was selected as the “best” representative of his time) was insufficient for an industrializing nation such as the United States. Bancroft’s historical focus was not just too religious, idealistic, and rigid, but it also failed to address economic circumstances and rang hollow and empty to a modern sophisticated profession. As the Gilded Age progressed and the impact of wealth and power on the daily lives of average people increased, the need for a far different approach to the idea of progress emerged in the field of American historiography. That America had not faced its last great crisis in the Civil War was clear in the minds of the Progressives who wanted to addresses the social ills produced by industrialization.

During the transition from Bancroft’s romantic theological concept of historical progress to the Progressive secularized view are a group of historians who brought professionalism to the craft and sought to bring the American historical profession to equal that of the great German historians. As done so with Bancroft, we will select a “best” representative of the group.

Part II coming tomorrow

[Footnotes removed so as not to allow someone to use this paper.]

This is actually taking a lot longer than originally expected, according to a Recent Blog Post.