With so much talk recently of the United States’s involvement in the Middle East and how it violates our Founding principle of “isolation,” I had an interesting discussion recently with my students concerning the historical theme “Isolationism.”

With so much talk recently of the United States’s involvement in the Middle East and how it violates our Founding principle of “isolation,” I had an interesting discussion recently with my students concerning the historical theme “Isolationism.”

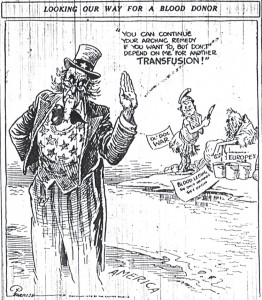

The debate centered on whether or not the United States has always been an isolationist nation? On the surface it is very easy to show cause and effect and change over time with regard to American foreign policy.

But seeing that we are expected to teach (here in Colorado, at least) “Isolationism” as a foregone conclusion, the question stands, “Isolationism, The Myth of the Founders?”

If we first consider George Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality (1793) and his belief that United States should act”friendly and impartial” towards any “Belligerent Powers.” Washington was being prudent, if you consider the year you know that the United States is but a fledgling nation having just created a Constitution and Bill of Rights. It was struggling to maintain itself. Though his cabinet was somewhat split on who to support in the European conflict between England and France, the road to Neutrality was the obvious one, to be sure.

As President Washington signed the first American Neutrality Act (1794), he seemingly established the tradition of isolation. Moving forward to Washington’s Farewell Address and his appeal to the Nation to keep America’s involvement in “permanent alliances” to a limit, “which to us have none or a very remote relation,” and recommend a policy “to steer clear of permanent Alliances,” the case seems closed.

And, if that does not solidify the argument in favor of America being an “Isolationist” nation, Thomas Jefferson followed up Washington proclaiming that “peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations,” was the goal and to avoid “entangling alliances with none.”

However, as should be noted, neither Washington nor Jefferson had any understanding of “Isolationism” as the word had not yet made it into the English vernacular. Both would arguably have issues with suggesting that the United States be “isolated” from Europe. Both looked to expansion in the West and the continued immigration of Europeans to their “Empire of Liberty” for settlement.

And Jefferson, as was his way, proved to be the enigma as he would send the U.S. marines to “the shores of Tripoli” to rescue Americans kidnapped by Barbary (Muslim) Pirates and to protect American commerce. He would unconstitutionally purchase the Louisiana Territory, an expansion that guaranteed the United States would probably be involved in foreign affairs. Jefferson, in particular, wanted the continued importation of European culture — hardly the stance of an ideologue bent of isolation.

From our involvement as a fledgling colony in the first World War (Seven Years War) to our ideological involvement in the first world crisis after independence: the French Revolution. Perhaps “Isolationism” is but a myth.

The United States of the late 18th and early 19th centuries could not afford an active role in foreign affairs, and perhaps had never intended to be as “isolationist” as we teach our students on a yearly basis.

Read more: http://www.americanforeignrelations.com/E-N/Isolationism-The-myth-of-the-founders.html

George Washington recognized the advantages of the United States’ geographical separation from Europe, and its chaste history regarding established alliances and enemies. In setting the initial course for American foreign policy, Washington favored, in his State of the Union Address to remain free of both.

And his successors generally agreed. While Jefferson favored an alliance with France to protect the fledgling nation from the threat he and others perceived remained from England, that alliance was the only permanent treaty entered by the United States with a foreign power for 165 years: until the formation of NATO in 1949. That indeed is a remarkable accomplishment, Exceptional even. This allowed the country to develop its institutions, and resist drains on the economy such as a standing army and navy. Meanwhile, it saw to the expansion of its borders, stretching eventually to the Pacific.

President James Monroe issued The Monroe Doctrine, which served as the guiding principle of US Foreign Policy, and was successful in its mission – preventing further colonization by European powers in the Americas, and likewise foregoing any colonization ambitions by the United States itself.

Teddy Roosevelt in 1905 (date) issued his Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, maintaining the “hands off” half of the Monroe Doctrine, but allowing for the United States to expand its influence over Latin America. It was immediately before T.R. that the US began to veer from the Monroe Doctrine. The Spanish American War, the Philippines, Cuba = the beginnings of imperialism, and the end of Exceptionalism as regards foreign policy.

Pingback: Interesting Stuff … | What Would The Founders Think?