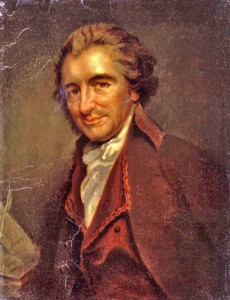

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” wrote Thomas Paine. These and other words by Paine were powerful and inspiring, but also alluring and engaging ideas that easily swayed thousands of colonists in 1776 and 1777 to join the Revolution.

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” wrote Thomas Paine. These and other words by Paine were powerful and inspiring, but also alluring and engaging ideas that easily swayed thousands of colonists in 1776 and 1777 to join the Revolution.

Thomas Paine’s popularity today among historians and readers of early American history has numerous origins. It’s not hard to imagine why? He never owned slaves and immediately on his arrival (late 1774) denounced slavery and even joined Benjamin Franklin as a member of Franklin’s anti-slavery society. Paine also was an outspoken critic of the English Crown, parliament and its corruption, but most importantly for modern social historians, he was an advocate of the poor, the downtrodden. His ability to offer clarity, context, and relevance to the debate over separation from the mother country of England for the colonists was essential to the popularity of his famous pamphlet, “Common Sense.” His words would have inspired those Revolutionaries already decidedly for independence, and the simplicity and force of his argument would have swayed those who were “on the fence.” The Loyalists would have, most likely, stayed loyal regardless of Paine’s argument.

The “reach” of Paine’s pamphlet alone is relevant to the question surrounding this paper: Would I have been swayed by Paine’s writing? Seeing that 1/5 of all colonists read Paine’s pamphlet, it’s a safe bet that I would have been able to acquire a copy of the text. Additionally, reach does not only apply to the physical ability to find the pamphlet, but also the ability to grasp its meaning. As we know, Paine’s writing style was very accessible to the average person. His prose “appealed to a cross-section of people: to artisans, craftsmen, and tradesmen as well as to bankers, manufacturers, and industrialists.” Additionally, most colonists could read and they enjoyed their local newspaper and visited coffee shops where politics were freely discussed. Word of Paine’s pamphlet would have spread quickly and his words debated.

Colonial society was ripe for separation from England. America was a “provincial” society that took pride in its “Englishness,” yet by the 1760s most colonialists felt the distance between them and the motherland. They felt that they were secondary to their counterparts on the island. Indeed, the actions that would be taken by the Crown leading up to the publication of Paine’s pamphlet setup an explosive situation that only needed igniting. Paine’s words would be that spark.

Paine takes his readers down a path that has only one destination: independence. But first he must provide a context and a meaning for the average colonist to comprehend. He wastes no time in raising the stakes when he writes, “[the] cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.” Right away the struggle was not just about independence, but freedom and not just for America, but for all mankind. This was a stroke of genius on Paine’s part. He immediately frames the idea of independence within the context of a continuing and ongoing struggle for freedom that encompassed all human beings.

From there Paine begins to outline the very basic ideas of John Locke and others: that individual rights come from a “natural” law and not from a King or government. “Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness,” he wrote. Paine starts off with having very few positive things to say about government. He ends this argument stating that though government is necessary, the way it exists in England is corrupt and inept. This leads to the obvious question, Why? Who is to blame? In order for Paine to give a strong argument for separation from England, he has to give us someone to blame, someone to loath. To him the answer was obvious: King George and Monarchy itself. It would be easy for me to loath such a form of government after reading Paine’s arguments.

Part II of his discourse systematically attacked the Crown and in very damning language. The problem with a monarchy was clear to him, “for monarchy in every instance is the Popery of government.” Paine outlines the “evil” nature of hereditary governing and how unnatural and undesirable this form of rule is. It is oppressive and infringes on those natural rights that all citizens have. No, a monarchy simply won’t do for Americans.

Paine felt as if he had to layout this course of action for his fellow colonists. He felt that he had to convince them. It was for him a commonsensical way of thinking about the situation. As Paine tells us, “I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.” And then he goes about doing just that and for us to understand what needs to be done. If his fellow Americans could not understand that “TIS’ TIME TO PART,” than one gets the feeling that Paine would have had no sympathy for us. It was self-evident that an island cannot rule a continent. Keeping political ties with England simply for defense or for the illusion of kinship was not enough for Paine. These were illogical arguments. That he would bring these points up shows that the connection between America and England had been reduced to simply commerce and little more.

Staying under the rule of a King was subjecting one to idea that “the law is King.” The law should serve us the colonists, Paine argued. The natural rights of property and freedom for individuals, and the freedom to practice any religion went against the idea of the King. These Republican ideas were already commonly held in America and to continue being ruled by a monarchy from across the ocean was counter to the idea of America’s own understand of freedom and politics. It was “tyranny” in practice as evidenced by the actions of the King.

Paine continues his argument by outlining what a “just” form of government is and that it was upon us to “begin government at the right end.” To establish a true republic with the principles that were self-evident and where all men were created equal. The governed would elect their leaders and where the King was the law, the “law is [now] King” and not the other way around. Most astonishing of all, perhaps, was Paine’s foresight in calling for a Constitutional Convention.

Paine’s Common Sense pamphlet placed the idea of independence within a larger struggle. He gave it a context. Paine outlined why the current state of affairs was not sustainable. And in simple, yet fiery ways, Paine outlined the basic facts that Independence was inevitable.

[footnotes have been removed]

Type in “Samuel Adams” and do a google.com search and you are just as likely to come up with links and images referring to the Beer Company Samuel Adams.

Type in “Samuel Adams” and do a google.com search and you are just as likely to come up with links and images referring to the Beer Company Samuel Adams.