What was the Founder’s true understanding of “Natural Law” and how did it influence the creation of the American Constitution? Was it even a significant factor? Still today the influence of Natural Law on the Founders is downplayed or even ignored. Some even deny its importance in the development and creation of our Republic. John Hart Ely stated years ago that Natural Law and natural rights beliefs were not generally acknowledged during the 1780s and that it “probably was not even the majority view among [the] ‘framers’…” This essay will show how Natural Law informed and guided the Founders as they declared their Independence and then solidified their republic with a new constitution during 1787 to 1789.

What was the Founder’s true understanding of “Natural Law” and how did it influence the creation of the American Constitution? Was it even a significant factor? Still today the influence of Natural Law on the Founders is downplayed or even ignored. Some even deny its importance in the development and creation of our Republic. John Hart Ely stated years ago that Natural Law and natural rights beliefs were not generally acknowledged during the 1780s and that it “probably was not even the majority view among [the] ‘framers’…” This essay will show how Natural Law informed and guided the Founders as they declared their Independence and then solidified their republic with a new constitution during 1787 to 1789.

Additionally, I will show how religion and Natural Law went hand and hand in the development of the constitution. How both helped to shape the document’s structure and power, but also how the Founder’s believed that the main hope for a successful republic was in the hands of the people. That for the American Republic to survive and the constitution to succeed both relied on a virtuous people who were well educated and spiritual.

Finally, I will demonstrate how the constitution was not designed to separate religion from the state, but to protect religion from the state. Though a simple and seemingly obvious statement, today it seems befuddled and confused. The Founders never intended to protect its citizens from exposure to religious symbols, ceremonies, or practice. They would have encouraged Christian practices and teaching.

When the new constitution was presented to the American people immediately some Founders debated whether or not it violated the spirit of the American Revolution. Some feared the power of the executive branch could become a kind of king and “tyranny” would result. The Vice President’s role in the Senate was objected to as well. A list of grievances was given by Elbridge Gerry during one debate in which he listed the ways the Constitution threatened the people:

“1. The duration and reeligibility of the Senate. 2. The power of the House of Representatives to conceal their journals [transparency]. 3. The power of the Congress over the places of election. 4. The unlimited power of congress over their own compensations…” Gerry stated that he could settle those issues if it weren’t for the additional issues of the Congresses seemingly unlimited power per the “necessary and proper” clause (as we call it.) George Mason stood and sounded the loudest objection when he declared, “There is no Declaration of Rights, and the laws of the general government being paramount to the laws and constitution of the several States… the people [are not] secure even in the enjoyment of the benefit of the common law.”

Which, everyone in the House chamber knew, had everything to do with Natural Law and whether or not the Constitution would infringe on those inalienable rights. No one at the time would have denied the status of Natural Law and its influence in American Constitutionalism. Anti-Federalist Thomas B. Wait wrote to his Federalist friend, George Thatcher, “For God’s sake let us not deny self-evident propositions,” and later, “[n]o people under Heaven are so well acquainted with the natural rights of mankind, with the rights that ever ought to be reserved in all civil compacts, as are the people of America.”

But what is Natural Law as the Founders understood it? According to some Constitutional scholars the origins of Natural Law starts with the teachings and writing of Marcus Tullius Cicero. Cicero was the first important philosopher to diverge from Plato and Aristotle and theorize about a “future society based on Natural Law.” Cicero defined Natural Law as an “agreement with nature… [an] eternal and unchangeable law…for all nations and all times, and there will be one master and ruler, that is God…” For Cicero, the central force that holds society together was the love of God. Natural Law flowed from spiritual understandings. His teachings and writings are more Christian than Platonic. Cicero, like the Founders, believed that in order for Natural Law to flourish it required that society be “highly moral and virtuous.”

Benjamin Franklin wrote that “only a virtuous people are capable of freedom.” Thomas Jefferson on numerous occasions spoke of his countrymen’s “natural rights.” And as we will see, his Declaration of Independence was first and foremost an expression of Natural Law. The combination of Natural Law with the belief that virtue and Christianity were needed to maintain the proper state of nature and hence Natural Rights. This understanding had a central influence on the Declaration of Independence and the constitution.

Benjamin Franklin wrote that “only a virtuous people are capable of freedom.” Thomas Jefferson on numerous occasions spoke of his countrymen’s “natural rights.” And as we will see, his Declaration of Independence was first and foremost an expression of Natural Law. The combination of Natural Law with the belief that virtue and Christianity were needed to maintain the proper state of nature and hence Natural Rights. This understanding had a central influence on the Declaration of Independence and the constitution.

Both Federalist and Anti-Federalists believed in Natural Law, but where they differed was how the constitution interacted with those principles. For the Anti-Federalists the threat of a large central government infringing on those “natural rights” made them fear the power of government as outlined in the new constitution proposed in 1789. It wasn’t that they were non-believers in Natural Law that was the issue. Benjamin Rush noted that American’s natural rights could only be superseded with “their own consent, or from tyranny” and that the constitution “neither implies the former, nor creates an avenue to the latter.” Each side took the stance that they stood for natural rights as each side understood the importance to reflect those principles. What was at stake was whether or not Natural Law would be impacted by the new government. Anti-Federalist George Mason took part in 1776 in writing an 18-page declaration of independence for Virginia and in it they were clear as to the role of natural rights. A Mason led committee wrote that, “all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural rights, of which they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity.”

When looking at the intellectual origin of the American Independence movement, we can start with Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and other enlightened political thinkers and from there trace the origins of Natural Law. However, perhaps the best starting point for our purposes here is Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. Paine’s pamphlet was the intellectual turning point for Independence. In a very clear and straight forward presentation Paine provided an emotional context for Americans and the revolution and did so by drawing from Natural Law: “I draw my idea of the form of government from a principle in nature.” It took Paine’s plain talk about the natural order of things and the obvious truth that government was not the source of individual rights, and together his words and the philosophy of Natural Law greatly impacted Americans and rallied support for the cause.

According to Gordon S. Wood, the “Revolution became a test of the Americans’ capacity for virtue.” It was one thing to claim natural rights and quite another to put it in place in the form of a government. Their sense of egalitarianism, they believed, took a familiar shape, though one from a long time ago. Americans consistently harkened back to classical times in public speeches and printed pamphlets. (James Warren wore a white toga during a speech shortly after the Boston Massacre.) John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in their letters and correspondences spoke of their “Ciceronian moment” that they hoped to achieve. The linkage between republicanism and Natural Law, to the Founders, was the understanding that virtue would be tested and that only a virtuous people could emerge from the Revolution with true independence. It was not wealth or bloodlines that determined leadership, but the qualities of a gentleman and his virtue. This would be central to American republicanism.

According to Gordon S. Wood, the “Revolution became a test of the Americans’ capacity for virtue.” It was one thing to claim natural rights and quite another to put it in place in the form of a government. Their sense of egalitarianism, they believed, took a familiar shape, though one from a long time ago. Americans consistently harkened back to classical times in public speeches and printed pamphlets. (James Warren wore a white toga during a speech shortly after the Boston Massacre.) John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in their letters and correspondences spoke of their “Ciceronian moment” that they hoped to achieve. The linkage between republicanism and Natural Law, to the Founders, was the understanding that virtue would be tested and that only a virtuous people could emerge from the Revolution with true independence. It was not wealth or bloodlines that determined leadership, but the qualities of a gentleman and his virtue. This would be central to American republicanism.

But what about the constitutional making process, do we see signs of Natural Law’s (natural rights) influence? Some recent scholars have denied Natural Law’s influence (such as Michael Perry) by pointing out that nothing in the constitution or Bill of Rights mentions natural rights or Natural Law. So if it was paramount to the constitution, than “a broadly accepted natural law philosophy surely would have found a place within [the Constitution], presumably in the Bill of Rights.” Yet some argue it is nowhere to be found or even succinctly expressed in the document.

First, let’s address what a constitution entails: 1) It establishes the form of government a state will use; 2) it outlines the powers of that government. The emphasis for us is on the second purpose of a constitution: power. Where does it come from and what rights do citizens have under that power?

As noted, the best place to start is the American Revolution or the dawn of it. During the Stamp Act Crisis several state legislatures put together resolutions outlining their rights and objections. One in particular is worth noting: “Resolutions of the house of Representatives of Massachusetts”, October 29, 1765. It starts off with four resolutions, and all are straight from Natural Law principles:

“1. Resolved, That there are certain essential Rights of the British Constitution of government which are founded in the Law of God and Nature, and are common Rights of Mankind – Therefore

2. Resolved, That the inhabitants of this Province are unalienably entitled to those essential rights in common with all men: and that no law of society can, consistent with the law of God and nature, divest them of those rights.

3. Resolved, That no man can justly take the property of another without his consent; and that upon this original principle, the right of representation in the same body which exercises the power of making laws for levying taxes, which is one of the main pillars of the British Constitution, is evidently founded.

4. Resolved, That this inherent right, together with all other essential rights, liberties, privileges, and immunities of the people of Great Britain, have been fully confirmed to them by Magna Charta, and by former and by later acts of Parliament.”

The very first resolution established the supremacy of Natural Law and God’s place as the deliverer of those natural rights. The second resolution stated that Natural Law cannot be denied to the people. The third resolution established property rights, something that the Founders believed was central to liberty, republicanism, and Natural Law. Finally, the fourth resolution established the chain of law that established natural rights.

In the same year, Pennsylvania produced a “Declaration of Rights” and it they declared that “all men are born equally free and independent and have certain natural inherent and inalienable rights…” Echoing the Declaration of Independence, they claimed that Natural Law assured one and all the access to “life and liberty” and the “pursuing and obtaining of happiness.”

As historian Jack N. Rakove has noted, the rights and confirmations assumed by Americans during the pre-Revolutionary period had their origins “in the authority of God or the law of nature.” But of course the most obvious document to examine is the Declaration of Independence. In Thomas Jefferson’s original draft he declared that he and his fellow countrymen enjoyed “inherent and inalienable rights” that did not originate with the Monarchy or any government for that matter. Though the words were changed somewhat to “certain inalienable rights,” it is clear the Founders were as a whole in agreement with idea of Natural Law.

Therefore, the first principle of our Constitution is Natural Law. For example, if we look at some of the major ideas and concepts of the American Constitution we see Natural Law’s influence abound:

“The concept of INALIENABLE RIGHTS …LIMITED GOVERNMENT…SEPERATION OF POWERS…CHECKS AND BALANCES… SELD PRESERVATION… is based on Natural Law”

The Constitution did not establish rights; it simply declared those that were “inalienable” and “self-evident” based on the Founder’s understanding of Natural Law. The power of the government was limited because it was not all powerful and it received its power from the people, popular sovereignty which was established under the beliefs of Natural Law.

However, all is not well with the constitution as the Founders knew it. Because only a handful of rights are outlined in the document and because of its vagueness and brevity, we have seen the judiciary have to determine if there was more (rights) to the Founder’s original declaration of rights? For example, though religion was clearly discussed in the constitution, the nature of those words is still contested today.

Though the Bill of Rights was seen by some at the time as an unneeded document, court rulings since its inception have rendered it one of the more important and controversial parts of our Constitution. With recent disputes over school prayer, Christmas celebrations, and debates on the “Christianity” of our nation, it seems prudent to examine, briefly, the Founder’s relationship with religion and what they saw as its role in society and specifically how it was an important element in Natural Law.

As noted earlier, virtue and morality were seen as important traits for any public to exercise a long lasting democratic and free republic form of government. So how did the Founders best believe a society could develop those traits? In 1787, the same year as the Constitutional Convention, the Congress passed what was called the Northwest Ordinance. Though a document that meant to establish sovereignty for the United States in the West, it also established several other things of note, in particular, Article III of the document, which reads in part:

“Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

Religious studies were established by the government as a necessity for proper education, which came directly from Natural Law doctrine and the belief that a virtuous and religious population was required to maintain an egalitarian republic. When Thomas Jefferson wrote his “Bill for Establishing Elementary Schools in Virginia,” he declared that “No religious reading, instruction or exercise, shall be prescribed or practiced inconsistent with the tenets of any religious sect or denomination.” Notice he did not say religion could not be practiced in school, only that it was done correctly. Jefferson was never against the promotion of religion, he wanted no religion or worshiper to be persecuted and for all religions to be protected. Jefferson’s thoughts on religion are important if we are to understand the true belief and place of religion in early American government and what the Founders intended for the role of religion in American society.

In June of 1776 Thomas Jefferson finished his third draft of a proposed constitution for Virginia, and in it he wrote:

“All persons shall have full and free liberty of religious opinion; nor shall any be compelled to frequent or maintain any religious institution.”

Clearly Jefferson wanted to protect one’s right to worship as they pleased and not be forced to worship. By 1779 Jefferson’s thinking on religion had expanded to protect not just one’s right to worship, but to express that belief. “[A]ll men shall be free to profess,” Jefferson wrote, “and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion.” He went on to declare their right to assemble and that these and other rights were “natural rights of mankind” and that an infringement on them was “an infringement on natural right.”

The clearest way to protect an individual’s right to worship was to make sure government could never infringe on that right. As we know, Natural Law depended on a virtuous and moral society and to protect the religious practices of Americans and the Founders made sure to be very clear on the government’s role in religion: it was hands off. In August, 1789, in the United States House of Representatives, a list of proposed Amendments to the Constitution was brought to the floor and in it was Article III, stating, “Congress shall make no law establishing religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, nor shall the rights of Conscience be infringed.”

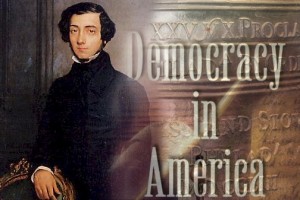

During his visit to America in 1831/32, Alexis de Tocqueville was often struck by American’s sense of not just freedom, republicanism and law, but also religion and how it intertwined with almost every fabric of American society.

“The Americans combine the notions of Christianity and liberty so intimately in their minds that it is impossible to make them conceive the one without the other; and with them this conviction does not spring from that barren, traditionary faith which seems to vegetate rather than live in the soul.”

Tocqueville mentioned American’s “lasting” faith and the spirit with which it lived in the country. He also found that in schools the teaching of religion took precedent and was important. While in New England he wrote, “every citizen receives the elementary notions of human knowledge; he is taught, moreover, the doctrines and the evidence of his religion,” along with the “history of his country.” Religion, education and government teaching went hand and hand with educating a people in a republic.

Tocqueville mentioned American’s “lasting” faith and the spirit with which it lived in the country. He also found that in schools the teaching of religion took precedent and was important. While in New England he wrote, “every citizen receives the elementary notions of human knowledge; he is taught, moreover, the doctrines and the evidence of his religion,” along with the “history of his country.” Religion, education and government teaching went hand and hand with educating a people in a republic.

The clear intent of the Founders was to protect religion, not to protect its citizens from the expression or practice of religion. James Madison, the Father of the Constitution and architect of the Bill of Rights, wrote that “There is not a shadow of right in the general government to intermeddle with religion.” No where do they mention that schools, government ceremonies, or any kind of public should be free of religious expression. The argument today for some becomes an ideological affair as they argue that there is a state sponsorship of religion if there is any kind of religious ceremony present in government agencies. However, nowhere does it say in the Constitution that religion and country shall be divided.

The idea of “separation of church and state” has been misconstrued. None other than Thomas Jefferson wrote that there must be “a wall of separation between church and state.” This and other writings by some Founders has been used, it seems, to justify the complete removal of religion from society. Slowly, religion has been completely removed from the classroom: Board of Education v. Allen (1968), established secular textbooks; Meek v. Pittenger (1975), stopped government funding of religious schools. Worst of all, using freedom of religion and the separation of church and state to allow students to not have to salute this country’s flag was established in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), and most importantly, Everson v. Board of Education (1947) where the court ruled quoting Jefferson’s “a wall of separation.” However, it is interesting to note that Virginia house representative Thomas Jefferson himself helped to write a bill that would have required a day of fasting and prayer. So did Jefferson mean that religion and state should be divided? Yes and no.

The concept of separation of church and state was not intended by Jefferson and the Founders to be used as a political and social tool to remove religion from places such as schools or government ceremonies. The idea of a “wall” was intended on a vertical level of constitutionalism, on the Federal level, and the establishing of a national religion. Both Jefferson and Madison wrote of religion’s proper place in society and even wanted states to be able to protect religious practices and ceremonies. For example, in his second inaugural address, Jefferson wrote:

“In matters of religion, I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the Constitution independent of the powers of the general government. I have therefore undertaken on no occasion to prescribe the religious exercise suited to it; but have left them, as the Constitution found them, under the direction and discipline of state or church authorities acknowledged by the several religious societies.”

The concern was if the federal government attempted to sponsor a religion that it might insight civil strife and disrupt the virtue of the people. Therefore, they left it to the states to decide. Perhaps most revealing of all is part of a letter written by Jefferson where he revealed his satisfaction concerning the use of a court house for religious practices:

“In our village of Charlottesville, there is a good degree of religion, with a small spice only of fanaticism. We have four sects, but without either church or meeting-house. The court-house is the common temple, one Sunday in the month to each.”

Even Jefferson, a man of questionable religious beliefs, supported time and again the need for religion in society, its open expression and practice, and was indeed supportive of fair religious practices, even when involving the role of government property.

In 1789 at President George Washington’s inauguration his Excellency finished by stating, “So help me God,” followed by Robert R. Livingston’s conclusion, “It is done, long live George Washington, President of the United States.” Yet today Liberal Scholars have begun attacking the legitimacy of this utterance (in a continuation of their attack on Natural Law) even calling it a “myth” that should be removed from American Historical memory. Historian Peter R. Henriques of George Mason University declared recently, “There is absolutely no extant contemporary evidence that President Washington altered the language of the oath as laid down in Article 2, Section 1 of the Constitution: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Henriques’ best argument is that Washington would never have drifted from the exact text. However, an equally engaging case could be made that as a Founding Father, a Christian, and most importantly a product of 18th Century America, Washington would have felt very comfortable in adding the words, “So Help Me God” to the oath. The fact of the matter is, we shall never know and any speculation otherwise to this accepted event of history, is just that.

On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to approve the United States Constitution and it was thus ratified. Interestingly enough, those fifty-five writers of the Constitution consisted of: twenty-six Episcopalians, eleven Presbyterians, seven Congregationalists, two Dutch Reformed, two Lutherans, two Methodists, two Roman Catholics, two Quakers and one supposed Deist –– Benjamin Franklin, who interestingly enough, called for prayer during the Constitutional Convention seven days later on June 28, stating, “I therefore beg leave to move – that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessing on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning.”

To separate church and state in 1789 at the levels we have today would have been a violation of the principles of Natural Law and would have destroyed, in the eyes of the Founders, the social fabric needed to maintain a virtuous and moral populace and therefore would have doomed their republic. The idea that there should be a “wall” separating church and state was never intended to take on the life it has today and one that has allowed for judges to legislate from the bench in an attempt to remove religion completely from American society and government.

In conclusion, the American Revolution took hold during a time of heightened sensibility to the order of Natural Law and, of course, republicanism. It is clear that not just the Founders, but many Americans, understood their rights in regard to a higher principle of Natural Law. The Declaration of Independence, the most important expression of the Revolution, was in step with the major tenants of Natural Law as outlined by Cicero. Our rights do not come from government, they are not something that is established, they are part of a natural order of things with God being the giver of all, according to the Founders.

The Constitutional Convention was the finalization of the Revolution and an event that solidified Natural Law’s predominance in American republicanism. The Constitution was an expression of the beliefs of most Americans, whether Federalist or anti-Federalist. Its major influence can be traced through many veins but all lead at some point to Natural Law.

Benjamin Franklin wrote that “only a virtuous people are capable of freedom.” The virtue of men was essential to maintain natural rights and the republic. The role of religion in American history is not debatable and the essence of our founding undeniable. From the early Puritan vision of a “House on upon a Hill” to the founding of the world’s first constitutional republic, Natural Law and religion were essential.

[footnotes have been removed]

I was reading this the other day and found that our society is forgetting so much about its “Exceptionalism” and part of it is in what Franklin is preaching below! Do you know what I mean?

I was reading this the other day and found that our society is forgetting so much about its “Exceptionalism” and part of it is in what Franklin is preaching below! Do you know what I mean?