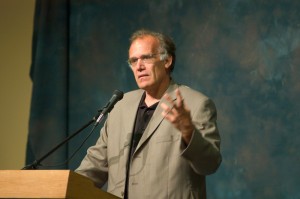

What follows is an email interview with Victor Davis Hanson who is one of our premiere military historians. More importantly, Dr. Hanson is the Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow of Classics and Military History at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and professor of Classics Emeritus at California State University, Fresno. Also, he is a nationally syndicated columnist for Tribune Media Services. As the Wayne & Marcia Buske Distinguished Fellow in History, Hillsdale College, he teaches each fall semester courses in military history and classical culture. Dr Hanson was recently awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2007 and the Bradley Prize in 2008.

What follows is an email interview with Victor Davis Hanson who is one of our premiere military historians. More importantly, Dr. Hanson is the Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow of Classics and Military History at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and professor of Classics Emeritus at California State University, Fresno. Also, he is a nationally syndicated columnist for Tribune Media Services. As the Wayne & Marcia Buske Distinguished Fellow in History, Hillsdale College, he teaches each fall semester courses in military history and classical culture. Dr Hanson was recently awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2007 and the Bradley Prize in 2008.

Additionally, Dr. Hanson is the author of numerous books, among them Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power, which in my opinion is a must read and a book that I find myself picking up often and referring to while I teach A.P. U.S. History and in particular my discussions of World War II with my students. Also, and the main reason for this interview, the upcoming book The Father of Us All: War and History, Ancient and Modern.

I hope you enjoy the interview.

B4H: As you stated in your upcoming book “The Father of Us All” war is rarely the result of miscommunication or misunderstanding. However, why was B.H. Liddell Hart wrong to state that “War is always a matter of doing evil in hope that good may come of it?” You did not agree with his statement.

VDH: I am not sure that using force to stop the SS is “a matter of doing evil”, especially in matters of self-defense. I know what Liddell Hart meant, but he phrased it wrongly: when a large bully attacks you and your loved ones, fighting back is a moral act; while begging for mercy or collapsing in a fetal position is a sort of evil thing that will result in the deaths of your dear dependents. So there is a sin of laxity as well as commission; as Aristotle reminds us being moral in one’s sleep is easy. Evil in 1939 was talk/talk/talk to Hitler while he planned to exterminate Poland.

As you noted, since the Peloponnesian War societies have sometimes convinced themselves that war would be short and that the enemy unwilling to commit to extended war. Is this getting worse today as modern societies adapt more “liberal” viewpoints? Has this really changed at all? Hasn’t this disillusionment always been a part of war?

As technology makes life better and the pace of our existences more rapid and rich, it is natural in such circumstances of impatience to think that war can be refined so that fewer are killed and its effects mitigated. Sometimes this is possible (cf. Panama or the Balkans); but human nature remains constant, so the old challenge/response cycle in which enemies react and escalate is still with us, along with those old human catalysts for violence—pride, honor, and envy. Going into the oil-rich, strife-ridden heart of the ancient caliphate to remove a thug and foster democracy is not quite the same thing as invading Grenada, so there will be times when all the high tech and sophisticated thought in the world won’t ensure an easy fight.

Why do democracies struggle to maintain prolonged war and is this not a serious issue from here on seeing that the nature of war has changed?

For a variety of reasons: 1) the people prefer their governments to spend money on themselves, far more easily defined as not spending dollars for tanks or bombs when there is a perceived need for social welfare programs; 2) democracy reflects majority opinion, itself fickle and predicated on popular perceptions: just as crowds get riled up and follow fads in mass fashion (see Thucydides book 2 on this), so they deflate suddenly as well when the promised benefits require more expense than anticipated; 3) majority votes often lead to sudden decisions. Herodotus said it was easier to persuade thousands of democrats at Athens to go to war than a few oligarchs at Sparta, the point being that once a majority is reached, it is very hard to question its legitimacy and action shortly follows, whether to abruptly go to war or to abruptly quit. Perhaps the greatest example of such democratic energy is a relatively unarmed America’s declaration of war in 1917, and then a million men in France by late spring 1918 (at rates of arrival in Belgium and France up to 10,000 doughboys a day).

All that said, when democracies find themselves in existential wars, in which their very survival is predicated on success, they are quite willing to mobilize to an astounding degree, whether Athens in 431 or America in 1941. The people’s nod is the public sanction, and there is no grandee or strong man to blame for the decision to fight.

I was taught that a military and the way it fights reflects the culture that produced it, is this still true? Why or Why not?

Yes, I think so with some qualifications as I wrote in Carnage and Culture. Culture–whether driving on the left side of the road or preferring mounted skirmishing to head-on infantry collisions–reflects popular mores, and to a lesser extent takes account of geography, terrain, and weather and national character. Our frontier, multiracial populace, radical democratic government, reliance on technology, and relative geographical isolation from Europe and Asia tended to make American armies eager to fight decisively, heavily reliant on machines, careful not to suffer casualties, mobile and rapid and eager to fight conclusively in order quickly to return home and demobilize.

Now with globalization, note that there is an increasingly uniformity in military practice as cultures start to blend into a Westernized pastiche. Just as we all agree that container ships are the most efficient methods of sea-borne commerce, so too the Western notions of military organization, high technology, and classical strategy and tactics tend to be embraced by most of the world. A soldier in Egypt is uniformed almost like one in Europe; a Vietnamese tank looks like an American model more or less; China flies Western-style jets, and even al Qaeda models its IEDs on concepts of Western land mines, parasitical as they are on things like Western cell phones, plastic explosives, garage door openers, propane canisters, etc.

Warfare has indeed changed: terrorism and insurgency have seemingly stifled the traditional Western way of warfare, has it not?

Yes, since classical times, tribes and poorer backwater states have plagued the military superior nation state in a variety of ways: they borrow, steal, and buy advanced technology (that they cannot make or often even repair) from Western powers; they can divide Western powers, or hope for a Civil War among them; they are often helped by anti-war movements, which call into question a consensual society’s moral or logical support for optional wars; they count on notions of asymmetry in which relatively more leisured and wealthy Westerners are less likely to submit to deprivation and risk early death than others for whom life is not so good–especially when war is fought at a distance and deemed by a public not to be a matter of national survival. Nothing we have seen in this context since 9/11 is thus new.

Is technology the answer to today’s unique warfare? Is there even an answer?

Technology is an accelerant, that closes the margin of error and nuances strategy and tactics; but that said, war is still fought by humans; their natures are unchanging; and thus the principles of what makes them fight, and why, and how they win or lose remain constant, mutatis mutandis. Predator attacks are very different from mounted archery ambushes, but their general aims—to take out key enemy leaders without committing resources to an all out war, remain the same across time and space. The challenge and response cycle between the IED and the up-armed American vehicle was as old as the catapult versus the stone-wall, albeit the time cycle collapsed from decades and centuries to mere days. Right now I am more worried about our planners being ahistorical and captives to technological determinism than obtuse to the role of rapidly changing machines.

You stated that “to begin studying war” the best place to start “is with the stories of soldiers themselves”. Why?

We have a tendency to see military history as a sort of art or abstract science, when it is legalized killing among very human participants. So to read about their first-hand experiences is to be reminded that war is a nasty business that is more than moving armies around on boards, although it is that too. There is a morality to military history that begins with understanding a lot of young people are going to die quite unfairly before their time, usually on their assumption that their premature ends are for a noble sacrifice for their loved ones to the rear. That perception should predate discussions of relative strength, balance of power, deterrence, alliances, etc. All these quite necessary referents derive from the general truth that, in the end, 18 year olds are going to kill someone and die. I think one learns as much about the face of war from E.B. Sledge as from Clausewitz, though both are necessary to understand war in general.

You said that most wars do not end as they start, is that not the nature of the beast? Wars rarely start and end for the reasons that the combatants initially thought? For example, the American Civil War and World War I. No one in 1860 would admit the war was about slavery, yet by 1863-64 it was indeed about slavery. Also, the reasons for fighting WWI if asked of a soldier in 1914 would changed significantly by 1918, did it not

Yes, as wars continue and the costs pile up, sometimes governments must reestablish the bases for war, adding new writs as others are deemed insufficient or no longer convincing; sometimes this is legitimate and honest as unforeseen enemies and issues arise—all predicated on ongoing success or failure. The Civil War was variously officially to be fought by the north to preserve the Union, to eliminate slavery in the Confederacy, to end slavery in both southern and border states, and finally to create a more perfect, more equal Union. What Union soldiers thought they fought for in 1865 was not quite the same as it had been in 1861. WWII started out to save Poland from Germany and Russia, and quickly ended up to save England and employ Russia to stop Germany. I don’t think anyone ever envisioned December 1941 ending up with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In summer 1950 the war was to save a small bunch trapped at Pusan not to fight on the Yalu 700 miles to the north; no one quite knows where wars will lead or why they transmogrify, so it wise to factor in the unpredictable from the start.

If there is no longer a need to plan for a “decisive battle” (as it is not longer practical) than why do modern military organizations still continue to develop massive armies, tanks, ect? When will we ever need to have a large armored or navy force?

I don’t think it is wise to see war as linear, as progressing from genesis A to a telos B, as if age-old tactics suddenly come to an end due to technological changes. Believe me, if tomorrow China invades Taiwan, North Korea crosses the 38th Parallel or Syria, Egypt,and Jordan send columns into Israel (all not impossible), lightly-armed counter-insurgency forces will be of little help: we will want tanks, planes, missiles, and howitzers—and plenty of heavy army divisions. Decisive battle on a grand scale is more difficult with satellite observation, globalization of the economy, would-be international law and morality, and the nuclear genie, but still possible and perhaps very likely soon. We need to be prepared for all contingencies with the ancient wisdom that the last war is not a sure guide for the next.

Is it time for the United States to consider withdrawing from its world leadership position and maintain a pre-WW2 isolationist position?

Been there, done that, and we know where it leads—more so now in the nuclear age. Like it or not, our 70-year policy of opposing tyrannical anti-Western, and often authoritarian nations abroad, rather than wait for their aggression to hit our shores, is far preferable in the long-term calculus of costs to benefits. Take the most controversial wars imaginable—Iraq and Afghanistan—and one can still distill that our proactive efforts to stop jihadism and the Middle East cycle of dictators abetting terrorists and disturbing the region have led to lots of insurgents and terrorists killed, no major attack on the US home soil, two of the worst governments who riled up anti-Americanism into two of the better governments in the region. I am glad today Noriega has not had two more decades of mischief in Panama, or Milosevic another decade to destroy the Balkans or Saddam another seven years of endless chances to recycle his petro-wealth into both regional war and support for terrorists.

Why?

Why engagement rather than isolationism? Wars are prevented by redlines, or active engagement with would-be belligerents in which aggressors accept that certain behaviors will earn a counter-response, whose effects are not worth the saber-rattling risk. If such deterrence is real and known to the enemy, then a Hitler, Stalin or Mao is less likely to start a war in the first place. Take most wars—the Falklands War or Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait—and one can find its genesis in the miscalculation of a belligerent who, quite logically, but wrongly, took initial signs of his opponent’s weakness or indifference as a argument to take a risk, in a sort of cost/benefit analysis. Had the Thatcher government said to Argentina that any attack on the Falklands would lead to a massive British air and naval response against Argentinan forces anywhere in the south Atlantic, or had Ambassador Glaspie warned Saddam that invading Kuwait would earn him the bombing of Baghdad, and had they been able to convince Gen. Galtieri or Saddam Hussein of their seriousness, then perhaps the subsequent wars might have been prevented. Nothing is for certain in war given human fickleness, but as a rule preparedness, deterrence, clear signals to would be aggressors, and a willingness to make sacrifices to avoid larger catastrophes tend to prevent wars or mitigate their severity.

Finally, where do you see the United States in 20 years, both militarily and politically?

I think it will be militarily preeminent, but its supremacy won’t be unquestioned when a billion-person China or India can marry their newly energized capitalist economies and limitless manpower to high-tech, Western weaponry. Our status ultimately hinges on the degree that we maintain a free market, productive economy, encourage immigration of the risk-taking and entrepreneurial, avoid tribalism and social unrest, and retain a tragic sense that military forces are necessary as a deterrent against greater evils than peacetime military expenditure. Clearly much of this depends on a competitive educational system that instill a tragic sense of self, rather than the current trends to a therapeutic curriculum that emphasize questions of self-esteem in lieu of imparting facts and inductive methodologies.