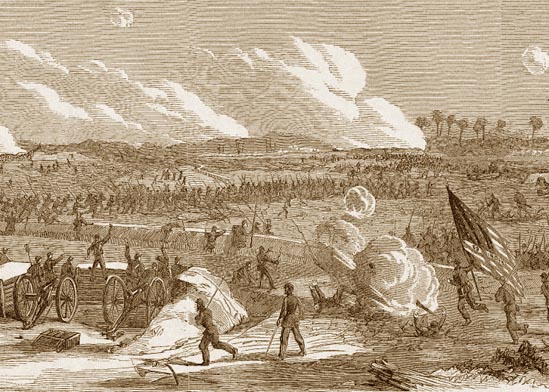

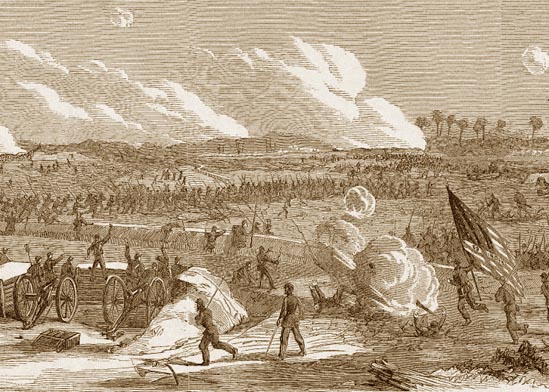

The attack on Fort Blakely during the late afternoon hours (5:30pm) of April 9th 1865 had no impact on the outcome of the war, yet the fighting was as viscous as any had been. In the post war years accusations of atrocities committed by black troops on white Confederates surfaced. The eye witness accounts were uneven and at times disputed. Even to this day, the degree of atrocities, if any, are still in dispute.

The attack on Fort Blakely during the late afternoon hours (5:30pm) of April 9th 1865 had no impact on the outcome of the war, yet the fighting was as viscous as any had been. In the post war years accusations of atrocities committed by black troops on white Confederates surfaced. The eye witness accounts were uneven and at times disputed. Even to this day, the degree of atrocities, if any, are still in dispute.

A 1998 article in America’s Civil War by Thomas G. Rodgers titled, “Last Stand at Fort Blakely,” the author skirts, for the most part, the racial aspects of the fight. Rodgers simply noted that the black troops charged as they yelled “Remember Fort Pillow” and that the Confederates were fearful of these former slaves. Some Confederates were bayoneted the author admits, and 2 white officers killed while trying to restrain the Negroes. But for the most part Rodgers stays away from the more controversial aspects of the fight, even at one point ending a quote prematurely. He quotes a Union officer who recalled a Confederate officer yell out, “Lay low and mow the ground…” Only Rodgers leaves out the most explosive part, as the entire quote was “Lay low and mow the ground—the damned Niggers are coming!” The battle started and ended as its own private race war/conflict.

In Fox’s Regimental Losses, it is meekly mentioned that “the closing battle of the war–the victorious assault on Fort Blakely, Ala., April 9, 1865–a colored division bore a conspicuous and honorable part.” Which is not a surprise, however, most accounts tend to follow suit and steer clear of the controversial and racial aspects of this fight. In a way, it was the first race conflict of the post-Civil War era. All participants involved knew the war was in its final stages, each wanting to wage its own private war.

Chaos reigns supreme during any battle, but this one took on a sharper edge as Confederates began to flee from the lines in fear of capture. Chaos turned into desperation at times, both for those who fled and those who stayed and fought to the death. “Rebels in front of the colored troops rushed towards the center for surrender as the cry of Fort Pillow with a red flannel rag on the end of a musket of the colored troops was not very encouraging for the Rebel chivalry, and to the credit of the colored troops, be it said General Hawkins Division did as well as any,” thus wrote Henry Carl Ketzle of the 37th Illinois Volunteer Infantry after the “last” great charge of the Civil War at Fort Blakely, Alabama.

A Confederate survivor described the fighting as the “Yankee Fort Pillow.” Reports of bayoneting and executing Confederate prisoners are not uncommon even by some Federal white troops who witnessed the events.

However, time and again the Negro troops are described by their white counterparts as having “distinguished themselves” with one going so far as to say they did the most “by capturing much of Fort Blakely.” By far most accounts by white Federal soldiers were ones praising the fighting of the black soldiers. One in particular after noting their fighting prowess and the atrocities declared, “who can blame them [the former slaves].” They were seeking to lay some deed at the alter of slavery.

But still, those positive reports cannot diminish the bloody nature of the fighting that day. After being captured a soldier with 62nd Alabama Volunteers noted years later, “We were guaraded by negro troops, most of them being from the South. They cursed us and called us by all vulgar names they could think of, even calling us ——— and we had to take it or be shot.” He was lucky to have survived. Many, fearful of those former slaves now armed in blue, either fought to the death, fled to the river and drowned, were shot down, or executed when captured.

The fighting was short, but intense and emotions ran high for both white and black Union soldiers. The Confederates had buried landmines in front of the fort and along the roads leading to the fort that for days before the fight randomly went off and killed dozens and caused much disgruntlement for both white and black soldier. Tensions were high and numerous white troops noted as such in their letters. When the 119th Illinois Infantry entered the fort after a hailstorm of fire and explosions from landmines, “Capt. Henry Cross, who had just seen his chum, John Myers, torn to pieces with a grape shot, greased his bayonet with the fattest of the gunners. ” [link]. White soldier’s easily lost their cool and were not immune to murdering prisoners and it is not hard to imagine the same from their black counterparts.

Just earlier this year an article in the Alabama Heritage magazine (Winter) by Jim Noles dealt with the “Fall of Fort Blakely.” Once again the subject of race and warfare was sidestepped for the most part. The highly charged quotes that could have been used were ignored. Noles does do a far better job than Rodgers, however, writing that “the allegation of captured Confederate troops being murdered by vengeful Union troops, particularly USCT soldiers” would plague the battle for most of the post-war period.

It should be noted that both Rodger’s and Noles’ focus was not on the nature of the fighting, but the events that led up to the fight and the outcome of the fight.

The fighting at Fort Blakely was a fairly rare event in Civil War history as the taking of the fort was determined mainly by hand-to-hand combat. Most Civil War combat was from a distance of several hundred yards and when charged, lines often broke and soldier’s fled [See Brent Nosworthy's The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War, (2005), 587-589; Also, 95% of all wounds reported during the Civil War were from bullets, see "Effects of Battle: Wounds, Death, and Medical Care in the Civil War," by Bruce A. Evans, M.D., Battle: The Nature and Consequences of Civil War Combat, (University of Alabama, 2008), 68-89]. In some parts of Fort Blakely the fighting raged for 10 to 15 bloodied minutes as Yankee and Confederate troops wanted more than ever to get one last lick in before the war was over. For indeed, all involved knew the war was winding down — just earlier in the day (though unbeknownst to the participants at Blakely) Robert E. Lee had surrender to Ulysses S. Grant. The war had been 4 long and bloody years and many regiments involved like the 11th Wisconsin, had participated in all four years of fighting. That revenge was on the minds of some, both black and white, is not hard to imagine.

[Note: I am not sharing a lot of citations as I am in the process of writing an article on Fort Blakely. I have already extensively researched this battle due to the involvement of the 11th Wisconsin, whom I wrote about several years ago.]

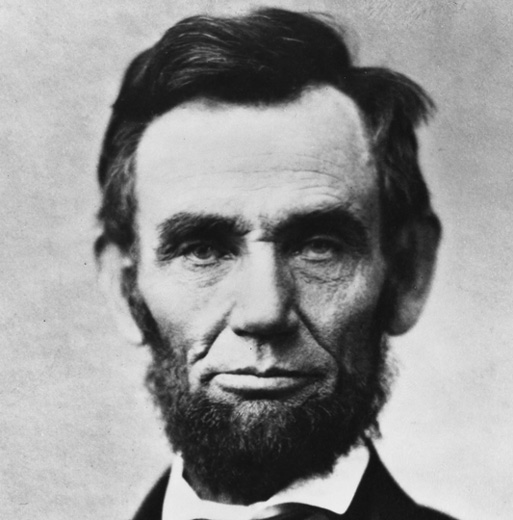

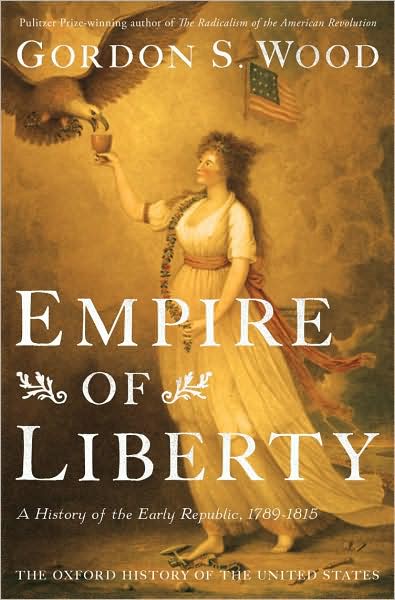

Some historians and wanna be historians love to do the “I told you so” in regards to American history. They love to point out how Lincoln was not the Great Emancipator, Washington did tell lies, and that Jefferson not only owned a bunch of slaves, he fathered children by one of those slaves. Indeed, all of the above observations are mostly true and have been corrected as such by social historians during the past several decades. For as we know, though Lincoln played a role in emancipation, he cannot be given much credit, Washington loved to tell lies and during the Revolutionary War he depended on telling as many lies as possible, and finally, Jefferson and Sally indeed had a sexual relationship that probably included rape. All of this is cause enough, for some, to remove them from their pedestal and probably remove them as being worthy of much study.

Some historians and wanna be historians love to do the “I told you so” in regards to American history. They love to point out how Lincoln was not the Great Emancipator, Washington did tell lies, and that Jefferson not only owned a bunch of slaves, he fathered children by one of those slaves. Indeed, all of the above observations are mostly true and have been corrected as such by social historians during the past several decades. For as we know, though Lincoln played a role in emancipation, he cannot be given much credit, Washington loved to tell lies and during the Revolutionary War he depended on telling as many lies as possible, and finally, Jefferson and Sally indeed had a sexual relationship that probably included rape. All of this is cause enough, for some, to remove them from their pedestal and probably remove them as being worthy of much study. A week or so ago the Pew Global Attitudes Project

A week or so ago the Pew Global Attitudes Project  I have found out today that my efforts to start an early American History survey course has been approved. Some of you who already have such a thing might be saying, “So What.” Thus, allow me to explain.

I have found out today that my efforts to start an early American History survey course has been approved. Some of you who already have such a thing might be saying, “So What.” Thus, allow me to explain. I recieved from

I recieved from  Sounds like Richard Dreyfuss was a complete bomb today at Kevin Levin’s private school in Virginia. Levin and his school had the unfortunate pleasure (I guess) to have this Hollywood actor/ historian (?) as a guest speaker. Levin titled his blog story today as

Sounds like Richard Dreyfuss was a complete bomb today at Kevin Levin’s private school in Virginia. Levin and his school had the unfortunate pleasure (I guess) to have this Hollywood actor/ historian (?) as a guest speaker. Levin titled his blog story today as  Recently Clint Eastwood, famed Hollywood actor and now director / producer, was interviewed for a cover story by

Recently Clint Eastwood, famed Hollywood actor and now director / producer, was interviewed for a cover story by  The attack on Fort Blakely during the late afternoon hours (5:30pm) of April 9th 1865 had no impact on the outcome of the war, yet the fighting was as viscous as any had been. In the post war years accusations of atrocities committed by black troops on white Confederates surfaced. The eye witness accounts were uneven and at times disputed. Even to this day, the degree of atrocities, if any, are still in dispute.

The attack on Fort Blakely during the late afternoon hours (5:30pm) of April 9th 1865 had no impact on the outcome of the war, yet the fighting was as viscous as any had been. In the post war years accusations of atrocities committed by black troops on white Confederates surfaced. The eye witness accounts were uneven and at times disputed. Even to this day, the degree of atrocities, if any, are still in dispute.

Well last night I spent several hours downloading, installing, and upgrading my WordPress so I could use one of the newer themes that required the newer version of WordPress. So the blog was down last night for some time and if you visited you would have seen several different looks and lots of confusion. Anyway, not done completely updating and tweaking this new look, but I like it. I like to keep the look consistent, but eventually a new look is refreshing and appealing. I hate sites that change every other week.

Well last night I spent several hours downloading, installing, and upgrading my WordPress so I could use one of the newer themes that required the newer version of WordPress. So the blog was down last night for some time and if you visited you would have seen several different looks and lots of confusion. Anyway, not done completely updating and tweaking this new look, but I like it. I like to keep the look consistent, but eventually a new look is refreshing and appealing. I hate sites that change every other week.