In honor of Washington becoming the first elected President on this day (1789).

The best strategy employed during the early stages of fighting was more akin to modern guerrilla style than the traditional European tactics of the day. The murderous sniper attacks of the Patriots on the British during their return from Concord were devastating. (Gen. Nathaniel Greene would use hit and run tactics with great success in the Southern Theater in the 1780s). Arguably the best performances by American commanders in 1777 were Gen. Hartio Gates and future traitor, Gen. Benedict Arnold. Both men played key roles during the Saratoga Campaign (October, 1777), whereby using similar hit and run strategies surrounded and defeated British Gen. John Burgoyne. The defeat and surrender of Burgoyne’s army (6,000 British and German troops) is credited with gaining French support that would be key for American victory in the war. During this same time Washington was facing defeat yet again at Germantown and forced to give up Philadelphia.

Very early on Washington (when he took command) favored the decisive battle strategy. Thinking he could maneuver the British into making another head on charge like Bunker Hill, but on a much large scale, dominated Washington’s mindset. This strategy would prove nearly fatal for the American cause. One could even argue that luck was the only thing standing between Washington and utter defeat during 1776-1777.

The generalship displayed by Washington in and around New York in 1776 was best described by none other than John Adams when he declared, “our Generals were out generalled.” But it was really one general who should have received Lion’s share of the blame, as Washington committed several near fatal mistakes. First, he divided his army in two, thus providing a competent General the opportunity to divide and conquer. Luckily for Washington, he was facing no such general in William Howe who was incompetent. Had Howe unleashed his army and attacked boldly, he could have possibly ended the Revolution in New York in 1777. Second, though half of his army at Long Island was fairly safe, the other half on Manhattan was trapped. Howe cut off Washington’s only escape route and though urged by subordinates to attack, demurred and allowed Washington ample time to formulate a late night crossing of the East River. Howe was incapable of taking advantage of Washington’s blunder and this allowed him time to get his army across.

The generalship displayed by Washington in and around New York in 1776 was best described by none other than John Adams when he declared, “our Generals were out generalled.” But it was really one general who should have received Lion’s share of the blame, as Washington committed several near fatal mistakes. First, he divided his army in two, thus providing a competent General the opportunity to divide and conquer. Luckily for Washington, he was facing no such general in William Howe who was incompetent. Had Howe unleashed his army and attacked boldly, he could have possibly ended the Revolution in New York in 1777. Second, though half of his army at Long Island was fairly safe, the other half on Manhattan was trapped. Howe cut off Washington’s only escape route and though urged by subordinates to attack, demurred and allowed Washington ample time to formulate a late night crossing of the East River. Howe was incapable of taking advantage of Washington’s blunder and this allowed him time to get his army across.

Washington’s generalship at this time was indecisive, stubborn, and foolish. Gen. Nathaniel Greene urged Washington to conduct a speedy retreat, but inexplicably he delayed. Washington then called a war meeting and allowed his generals to vote, and they did so in support of Greene. Though appearing to give in, Washington ultimately decided to stay and fight it out. As historians have noted, “Washington’s decision to linger on Manhattan was militarily inexplicable and tactically suicidal.”

The inexplicable behavior on the part of Washington did not end there. Though lucky to get his army out of the jaws of defeat, he decided to keep Gen. Greene at Fort Washington with orders to hold at all costs. The result, it fell and 3,000 patriots were killed and/or captured. The effects of this defeat were devastating. Though Greene made the bizarre request to defend the fort, Washington needed to make the right choice and get all his men out. There was no way the fort was going to hold out and there was no way Washington would be able to come to its rescue. Though it delayed Howe long enough to insure his escape, Washington could have still outmaneuvered Howe and avoided defeat during his escape. One thing Washington was good at was his ability to maneuver his army.

But Washington lucked out, as Howe was not capable of taking advantage of Washington’s mistakes. Luck would be something that was consistently on Washington’s side. He was brave in battle and countless times had his horse shot out from under him, yet he survived battle after battle.

Even Washington’s so-called greatest victory at Trenton, 1776 was perhaps only gained by luck. The Hessian commander Gen. Johann Gottlieb Rall was notified by a Loyalist that an attack was coming, yet his order not to be disturbed delayed his reception of the intelligence in time to act. Weather put Washington three hours behind schedule and increased the chances of being discovered. Three of his four units never materialized having failed to cross the Delaware River, a near calamitous development that could have had drastic consequences. Washington’s plan was complicated and daring, and his leadership in battle honorable. However, though 800 plus Hessians captured, over 500 escaped. Had this force of 1300 been alerted and prepared, it is probable that the fight would have been extremely bloody and could have resulted in total defeat, as Washington once again placed himself with a river in his rear. Additionally, the victory was more morale than material. The loss of only 800 Hessians was minor compared to Saratoga.

Washington’s army was a shell of its former self at the end of 1776 with just a few thousand men healthy enough to fight. The year of 1777 was not much kinder. Defeats at Brandywine, Germantown, and the loss of Philadelphia were demoralizing for Washington’s army. Wherever the British army wanted to go, Washington seemed incapable of stopping it.

But luckily for the fledgling United States, and Washington, he was not removed from command when one could argue he should have been. Washington would develop his Fabien strategy, though reluctantly, and outlast the invaders. He would win the war. His generalship improved along with his ability to adapt. In the end, Washington was the right person in the right place and at the right time. But, nonetheless, perhaps he should not have been. Imagine how different our history would be without him after 1777.

Using data from 395 daily U.S. newspapers the Audit Bureau of Circulations reported today a declined of 7.1% for October-March in daily newspaper circulation from the same six-month span in 2007-2008. It cited that The New York Times circulation fell 3.6 percent to 1,039,031, while the Los Angeles Times faded 6.6 percent to 723,181. (

Using data from 395 daily U.S. newspapers the Audit Bureau of Circulations reported today a declined of 7.1% for October-March in daily newspaper circulation from the same six-month span in 2007-2008. It cited that The New York Times circulation fell 3.6 percent to 1,039,031, while the Los Angeles Times faded 6.6 percent to 723,181. (

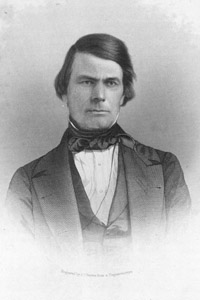

Hiram Warner was a Representative from Georgia born in Williamsburg, Hampshire County, Mass., on October 29, 1802. He was appointed by Governor Jenkins as judge of the Coweta Circuit Court and served from 1865 to 1867, when he was appointed chief justice of the State supreme court and was subsequently elected and served until 1880, when he resigned; died in Atlanta, Ga., June 30, 1881; interment in Town Cemetery, Greenville, Meriwether County, Ga.

Hiram Warner was a Representative from Georgia born in Williamsburg, Hampshire County, Mass., on October 29, 1802. He was appointed by Governor Jenkins as judge of the Coweta Circuit Court and served from 1865 to 1867, when he was appointed chief justice of the State supreme court and was subsequently elected and served until 1880, when he resigned; died in Atlanta, Ga., June 30, 1881; interment in Town Cemetery, Greenville, Meriwether County, Ga.