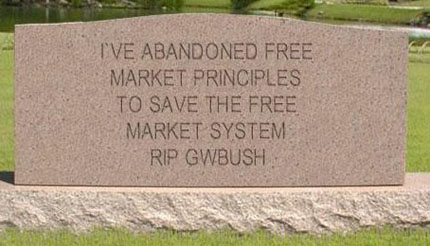

Howard Zinn is not a historian, he is a political activist. But then again, maybe he is no different than the rest of us, his is just being more honest.

In my graduate “Historical Research Methods” class we have had, as you can imagine, plenty of discussions on historical research and writing. We’ve been reading a lot about “objectivity” and honesty in the field of history. How we research and how we write involves more than just looking for something and arranging it chronologically or however.

Here are some random thoughts of mine based on what has happened over this weekend in regards to my stand on Zinn and history:

First, is historical “objectivity” truly attainable? Historians are first and foremost a product of something. They bring with them ethos and beliefs that permeate everything they do, this cannot be avoided. Alas, they are human.

Show me a teacher or a historian who says they are 100% objective, and I’ll show you liar. I just don’t think it possible anymore. At one time I did.

Peter Novick, in his excellent book That Noble Dream: The Objectivity Question and the American Historical Profession, traced the evolution of American historicism. Novick’s book is a tour de force, an incredible journey through American historical writing. As I made my way through his book I was struck by the obvious connection between social movements and history writing.

I also discovered myself sympathetic to some movements and not sympathetic to others. Why? (Sorry Fischer) Because ultimately I am a social and political animal and I am sensitive to some things, and sympathetic to others. Just as a historian would be.

For example, if you looked at history writing during the height of the Cold War from the late 1940s to the 1950s and compared it with the late 60s and 70s, you would see a clear break between two distinct approaches towards American History. Novick titled this chapter dealing with this time period: “Objectivity in Crisis.”

Before this time period, historians generally agreed on what Novick describes as “explanandum,” or “that which is to be explained.” There was a conservative belief in what should be taught. Therefore objectivity was rarely questioned.

By the 1960s, there was no longer a consensus. What emerged during this time was an “oppositional” movement; which helped the study of history move into areas of neglect: women, African-Americans, and the whole idea of history from the “bottom up.”

These “New Left” historians began to reinterpret the past. They tackled things such as McCarthyism and the origins of the Cold War, and did so without a bias in favor of the United States. Also, as we know, the 1960s and 70s was the time of the “counterculture” movement, and that this “new” history developed side-by-side is (of course) no coincidence.

This movement in history writing is important because it exposed the lapses in traditional historical writing. This time period also saw the evolution of “social history.” But this “new” history and the historians who wrote it became a part of the social movement and expressions of it. This was an incredibly exciting time to be a historian. These new historians saw themselves as champions of a cause. And indeed, they were helping to move history writing in American in a new direction.

These new historians were not so much concerned with “objectivity” because they felt that objectivity had been lost long ago; and indeed they may have been correct. They were seeking what they saw as a “truth.”

They saw themselves as political animals as well. To remain politically neutral was dishonest in their view. As Novick points out, they saw “Scholarly dispassion [as] the true medium of the scholar satisfied with things as they are.” The New Left historians were here to shake things up. And indeed they did, and have. Being “passionate” was a part of this new social and history writing movement.

This brings me to my second point, where does passion belong in the writing of history? I thought that without it you would have history void of a human quality. History was boring without a passionate storyteller.

Now I am starting to wonder if passion is what is wrong with history writing, both Right and Left. When I select a topic because I have a strong desire to see something or right a wrong, I cannot help but be helplessly biased in my approach. In my graduate class we looked at “The Rape of Nanking” from both a Chinese and Japanese view. This had a profound impact on me. History was being used as an emotional medium with tremendous amounts of passion and sometimes little evidence. Each culture fighting over how the event is remembered. Who owns history? Clearly both have a stake in how this event is written and both have a right to defend their viewpoint. Therefore, both are right and wrong. Each was being dishonest in order to protect their past.

My instructor is having us, I think, focus on the evidence and to allow it and only it to guide us. This process is void of passion and places us mentally in a very static position. Removing passion and a sense of social justice from our thinking is proving difficult. It takes the fun and excitement out of the research and the writing.

Finally, what is historical truth? Is it what historians deem worthy of study and what evidence is important or not? Are historians more guardians of social and/or political movements than truth seekers?

I want to leave you with a few quotes from selected readings. I don’t know if any of these fine historians is right or not, but it helps to at least confuse the subject even more than I have!

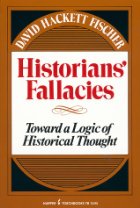

David Hackett Fischer, in his Historical Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought, wrote: “Most historians tell stories in their work. Good historians tell true stories. Great historians, from time to time, tell the best true stories which their topics and problems permit.”

Eric Foner, Who Owns History? Rethinking the Past in a Changing World, wrote: “Americans have always had an ambiguous attitude toward history. ‘The past,’ wrote Herman Melville, ‘is the text-book of tyrants; the future is the Bible of the free.’”

Barbara W. Tuchman, Practicing History, wrote: “If the historian will submit himself to his material instead of trying to impose himself on his material, then the material will ultimately speak to him and supply the answers.”

As

As

According to Fisher, there are, you guessed it, a range of assumptions that a lot of historians make when they are writing about history. These “fallacies” hopelessly doom the work of some historians as flawed.

According to Fisher, there are, you guessed it, a range of assumptions that a lot of historians make when they are writing about history. These “fallacies” hopelessly doom the work of some historians as flawed.