Recently I have been looking through a few books that have arrived (or been on the To Be Read Stack).

Recently I have been looking through a few books that have arrived (or been on the To Be Read Stack).

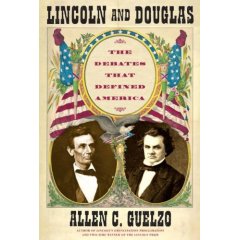

First, Allen C. Guelzo’s Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America. As a simpleton high school history teacher I am enjoying the careful development of Guelzo’s thesis as it centers on the nature of these debates and their representative aspect in understanding the social and political culture of the 1850s.

In 1858, the Lincoln and Douglas debates captured and enraptured America’s attention and consciousness over the issue of slavery. The debates were not just a representation of America’s mood and disposition, but also a reflection of the social element of the time period.

It would be difficult for most Americans today to imagine spending an entire evening listening to political discourse. It would be almost unfathomable to imagine this as a form of entertainment and enlightenment. In so many ways, the debates of 1858 are a perfect representation of American culture on the eve of the Civil War.

I have noted many times my belief that as teachers we have to be very careful with our presentation of Lincoln and the race issue. It is very easy to take something like the following quote (1858, Ottawa) and immediately condemn Lincoln:

“I will say here, while upon this subject, that I have no purpose directly or indirectly to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong, having the superior position.”

Parts of this quote have been used countless times in efforts to dismiss Lincoln as a racist and white supremist. Indeed, Lincoln was a racist and white supremist in every modern definition and understanding of the term; which is precisely the problem.

We have to take Lincoln on his own terms and view him within the environment that he was created in. If we can remove emotion and today’s standards of justice and moral understanding, then we can view his very next comment (after the above) with some enlightenment:

“I have never said anything to the contrary, but I hold that notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the Negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Lincoln was a progressive thinker and was always consistent in his desire to stop slavery’s expansion and his hatred for the institution.

Slavery’s existence in the United States in 1858 was a complicated issue that would take a lot of study for us today to even attempt to understand. I own the 1953 Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln and I have spent time reading the speeches and writings, and I can say that to truly do justice to Lincoln you have to not only read his words, but understand the context of them. This is where too many high school history teachers do an injustice to perhaps our greatest President.

Winston Churchill’s The Second World War, Vol. 1: The Gathering Storm was a great read as I was prepping for my U.S. History B section, where we start with World War II. For me, I do not know if you can teach the tragedy that is WWII well without reading at least a little of Winston Churchill.

Churchill was of course not just an observer, but also an actor during this tumultuous time. “The Gathering Storm” outlines the follies that allowed Hitler to rebuild the German war machine, harass and intimidate his neighbors, slowly plunge the world into another war, and attempt the extermination of a race. Meanwhile the world (League of Nations) did nothing, and in some ways facilitated him in his cause.

Churchill was one of the few who early on understood Hitler’s evil nature. And later he would also be correct in his assessment of Stalin, Why? Because Churchill was a historian and statesmen, not a politician!

In Vol. 1, Churchill makes his aim very clear, “It is my purpose, as one who lived and acted in these days, to show how easily the tragedy of the Second World War could have been prevented.” And then he sets out to do so: denial, appeasement, weakness, and wishful thinking (to summarize him). Today we can see some comparison with certain events and developments. I’m not going to go into any more detail on that.

Finally, a book I have had for some time and finally got around to reading, W. Cleon Skousen’s The 5000 Year Leap: A Miracle That Changed the World.

I love this book. It’s message is simple, yet important and the presentation is very effective. I also teach American Government and if it were up to me, I’d scratch our current 1996 book (yes it’s that old) and use this one for the class.

The miracle that was the founding of this country and the principles that made up that founding represent one of the truly magnificent developments in human history. Has our struggle to live up to these principles been one of total enlightenment? No, not always, and sometimes not even close. But it has been a wonderful experiment thus far, and one that has spread liberal democracy throughout the world and has improved the condition of humankind.

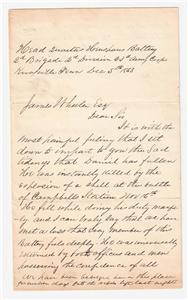

I haven’t seen a lot of these, and of the few I have, this one is a fairly representative one. I am not aware of the practice of writing KIA letters as a prominent occurrence, especially by the year 1863. It’s interesting how with just minor changes, this could have been a letter written during WW2 or any other 20th Century war. This letter represents the “Good Death” KIA correspondence. Not uncommon, especially with WW2 and Vietnam.

I haven’t seen a lot of these, and of the few I have, this one is a fairly representative one. I am not aware of the practice of writing KIA letters as a prominent occurrence, especially by the year 1863. It’s interesting how with just minor changes, this could have been a letter written during WW2 or any other 20th Century war. This letter represents the “Good Death” KIA correspondence. Not uncommon, especially with WW2 and Vietnam. Edward Winslow (1595 – 1655) was a Pilgrim of the Mayflower and a leader of sorts. He served as the governor of Plymouth Colony in 1633, 1636, and finally in 1644. I mention him as in 1624 he published “Good Newes from New England, or a True Relation of Things very Remarkable at the Plantation of Plimouth in New England” which detailed not just the history of the first Pilgrims, but also things concerning the local natives. In particular, Winslow described an experience of his while taking a walk along an Indian trial full of interesting landmarks, though they were much more than that. The Indians he was speaking of were the Pokanokets, and, I think you will find their attempt at preserving their heritage and history of interest, to say the least. Edward Winslow describes what he saw, p. 62:

Edward Winslow (1595 – 1655) was a Pilgrim of the Mayflower and a leader of sorts. He served as the governor of Plymouth Colony in 1633, 1636, and finally in 1644. I mention him as in 1624 he published “Good Newes from New England, or a True Relation of Things very Remarkable at the Plantation of Plimouth in New England” which detailed not just the history of the first Pilgrims, but also things concerning the local natives. In particular, Winslow described an experience of his while taking a walk along an Indian trial full of interesting landmarks, though they were much more than that. The Indians he was speaking of were the Pokanokets, and, I think you will find their attempt at preserving their heritage and history of interest, to say the least. Edward Winslow describes what he saw, p. 62: Recently I have been looking through a few books that have arrived (or been on the To Be Read Stack).

Recently I have been looking through a few books that have arrived (or been on the To Be Read Stack).