This is an article by Rick Atkinson, author of The Day of Battle, an excellent book that I am completely enjoying and will report on in more detail later.

Land of the Cyclops

Land of the Cyclops

By Rick Atkinson

Few Sicilian towns claimed greater antiquity than Gela, where the center of the American assault was to fall. Founded on a limestone hillock by Greek colonists from Rhodes and Crete in 688 b.c., Gela had since endured the usual Mediterranean calamities, including betrayal, pillage, and, in 311 b.c., the butchery of five thousand citizens by a rival warlord. The ruins of sanctuaries and shrines dotted the modern town of 32,000, along with tombs ranging in vintage from Bronze Age to Hellenistic and Byzantine. The fecund “Geloan fields,” as Virgil called them in The Aeneid, grew oleanders, palms, and Saracen olives. Aeschylus, the father of Attic drama, had spent his last years in Gela writing about fate, revenge, and love gone bad in the Oresteia; legend held that the playwright had been killed here when an eagle dropped a tortoise on his bald skull.

Patton planned a different sort of airborne attack by his invasion vanguard. On the night of July 9–10, more than three thousand paratroopers in four battalions were to parachute onto several vital road junctions outside Gela to forestall Axis counterattacks against the 1st Division landing beaches. Leading this assault was the dashing Colonel James Maurice Gavin, who at thirty-six was on his way to becoming the Army’s youngest major general since the Civil War. Born in Brooklyn to Irish immigrants and orphaned as a child, Gavin had been raised hardscrabble by foster parents in the Pennsylvania coalfields. Leaving school after the eighth grade, he worked as a barber’s helper, shoe clerk, and filling station manager before joining the Army at seventeen. He wangled an appointment to West Point, where his cadetship was undistinguished. As a young officer he washed out of flight school; a superior’s evaluation as recently as 1941 concluded, “This officer does not seem peculiarly fitted to be a paratrooper.” Ascetic and fearless, with a “magnetism for attractive women,” Jim Gavin was in fact born to go to the sound of the guns. “He could jump higher, shout louder, spit farther, and fight harder than any man I ever saw,” one subordinate said.

His 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, part of the 82nd Airborne Division, had staged in central Tunisia. Gavin harbored private misgivings about the Sicilian mission — “many lives will be lost in a few hours,” he wrote — and with good reason. The 82nd had received only roughly a third as much training time as some other U.S. divisions. The amateurish Allied parachute operations in North Africa had been marred by misfortune and miscalculation. No large-scale night combat jump had ever been attempted, and so many injuries had plagued the division in Tunisia — including fifty-three broken legs and ankles during a single daylight jump in early June — that training was curtailed. Much of the husky planning had been done by officers who had no airborne expertise and whose notions were suffused with fantasy. Transport pilots had little experience at night navigation, but to avoid flying over trigger-happy gunners in the Allied fleets, the planes, staying low to evade Axis radar, would have to make three dogleg turns over open water in the dark. Airborne units had yet to figure out how to drop a load heavier than three hundred pounds, much less a howitzer or a jeep. An experimental “para-mule” broke three legs; after putting the creature out of its misery, paratroopers used the carcass for bayonet practice. Still, the ranks “generally agreed that training proficiency had reached the stage where the mission was ‘in the bag,’” wrote one AAF officer, who later acknowledged “possible overoptimism.”

At about the time that Hewitt’s fleet neared Malta, Gavin and his men had clambered aboard 226 C-47 Dakotas near Kairouan. Faces blackened with burnt cork, each soldier wore a U.S. flag on the right sleeve and a white cloth knotted on the left as a nighttime recognition signal. Days earlier an 82nd Airborne platoon had circulated through the 1st Division to familiarize ground soldiers with the baggy trousers and loose smock worn by paratroopers. Parachutes occupied the C-47s’ seats; the sixteen troopers in each stick sat on the fuselage floor, practicing the invasion challenge and password: george/marshall. Dysentery tormented the regiment, and men struggled with their gear and Mae Wests to squat over honeypots placed around the aircraft bays. Medics distributed Benzedrine to the officers, morphine syrettes to everyone.

As the first planes began to taxi — churning up dust clouds so thick that some pilots had to take off by instrument — a weatherman appeared at Gavin’s aircraft to affirm Commander Steere’s prediction of lingering high winds aloft. “Colonel Gavin, is Colonel Gavin here? I was told to tell you that the wind is going to be thirty-five miles an hour, west to east,” he said. “They thought you’d want to know.” Fifteen was considered the maximum velocity for safe jumping. Another messenger staggered up with an enormous barracks bag stuffed with prisoner-of-war tags. “You’re supposed to put one on every prisoner you capture,” he told Gavin. An hour after takeoff, a staff officer heaved the bag into the sea.

Copyright © 2007 Rick Atkinson from the book The Day of Battle by Rick Atkinson Published by Henry Holt and Company; October 2007;$35.00US; 978-0-8050-6289-2

Rick Atkinson was a staff writer and senior editor at The Washington Post for more than twenty years. He is the bestselling author of An Army at Dawn, The Long Gray Line, In the Company of Soldiers, and Crusade. His many awards include Pulitzer Prizes for journalism and history. He lives in Washington, D.C. www.thedayofbattle.com.

Men of Fire: Grant, Forrest, and the Campaign That Decided the Civil War by Jack Hurst

Men of Fire: Grant, Forrest, and the Campaign That Decided the Civil War by Jack Hurst Land of the Cyclops

Land of the Cyclops I am not in agreement with some that Ken Burn’s new doc

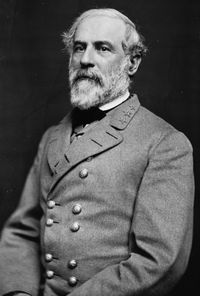

I am not in agreement with some that Ken Burn’s new doc  This was brought to my attention recently by a fairly heady student for a general U.S. History class in a public school. This student asked me how should Robert E. Lee’s success as a commander be measured? By how many times he persuaded inept Federal generals to leave the field and retreat, or by, say, casualty rates? This student had done some research and discovered that Lee, though commanding the field after many a battle, rarely inflicted a “higher” casualty rate. His casualties were almost always less and that was because he was almost always out-numbered.

This was brought to my attention recently by a fairly heady student for a general U.S. History class in a public school. This student asked me how should Robert E. Lee’s success as a commander be measured? By how many times he persuaded inept Federal generals to leave the field and retreat, or by, say, casualty rates? This student had done some research and discovered that Lee, though commanding the field after many a battle, rarely inflicted a “higher” casualty rate. His casualties were almost always less and that was because he was almost always out-numbered.