Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862, by O. Edward Cunningham and edited by Gary D. Joiner and Timothy B. Smith

Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862, by O. Edward Cunningham and edited by Gary D. Joiner and Timothy B. Smith

Savas Beatie, 2007

Hardback, 32 maps, photos, notes, appendices, bibliography, photographic battlefield tour.

Pp. 520

$34.95

ISBN: 1-932714-27-8

I presented a post here about the Battle of Shiloh as I was in the midst of reading O. Edward Cunningham’s “Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862,” which is the best book on Shiloh I’ve ever read. As the book’s editors point out, with only really three modern books written about the battle, [Wiley Sword "Shiloh: Bloody April" (1974, Revised 2001); James McDonough "Shiloh: In Hell Before Night" (1977); Larry Daniel "Shiloh: The Battle That Changed the Civil War" (1997)], it seemed appropriate to bring this already fairly well-known manuscript to print.

It’s strange to me that Shiloh gets such little recognition compared to the other severe contests of the war. Its outcome was significant for the campaign in Tennessee and had it turned out differently (if it had been a defeat for Grant) it could have had serious consequences on the war. On top of that, the reasons for its outcome are still to this day not agreed on by historians.

Edward Cunningham, a young Ph.D. candidate studying under the legendary T. Harry Williams at Louisiana State University, researched and wrote “Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 186″ in 1966. Now 41 years later it is finally in a format so everyone can enjoy it. Unfortunately, Dr. Cunningham did not get to see it as he died in 1997 – congratulations to Savas Beatie for doing so.

The book was edited by Gary D. Joiner, Ph.D., who is the author of several books, and Timothy B. Smith, Ph.D., and the author of “Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg” (winner of the 2004 Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Non-fiction Award). Both men do a fantastic job adding some additional depth and modern sources to notes. They also did remove and edit some of Cunningham’s original writing, which I am still not sure how I feel about that.

Cunningham’s narrative style is one of the things that surprised me. His writing carriers you in and out of the technical aspects of the battle effortlessly with a wonderful prose that includes tidbits of interesting details on the regimental and even the individual soldier levels.

This book is easily in the top 5 of Western Theater studies of the Civil War.

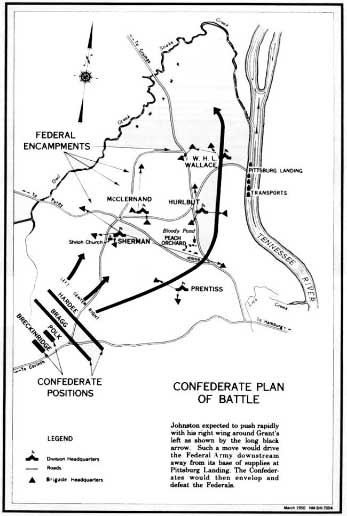

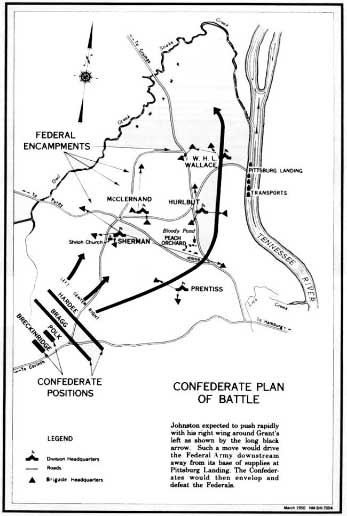

As the editors note, Cunningham’s work was ground breaking (and ahead of its time) in several ways. There are several different takes on the “keys†to the battle’s outcome. One school of thought suggests it was the staunch resistance by Prentiss and his men at the Hornet’s Nest and Sunken Road that saved the day for the Federals. Another school of thought says that the death of Confederate General A. S. Johnston determined the battle’s outcome. The third and final main school of thought points out the disarray and disorganization of attack and the lack of understand of the Federal’s positions as the most significant factor in the fighting’s outcome. In essence, Johnston had devised a faulty battle plan.

Cunningham’s work falls in with this last school of thought; only he did so forty years ago. He also is the first to suggest that the Sunken Road really wasn’t sunken and that it did not play a role in the battle. Even recent scholarship (Sword, 1974/2001) suggests that Johnston’s death was the key.

Though I am no expert and have spent minimal time looking at battle reports, soldier correspondences, and maps, I tend to agree with Cunningham that the planning of the attack probably played the largest role in the battle’s outcome. And I also agree with Cunningham that the inexperience of the Confederate soldiers also played a significant role. For the most part they were facing a well-trained, well-armed, and experienced Federal army.

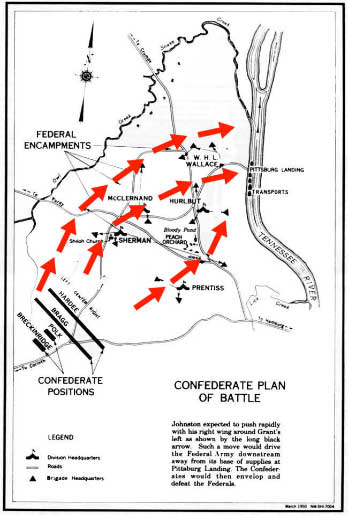

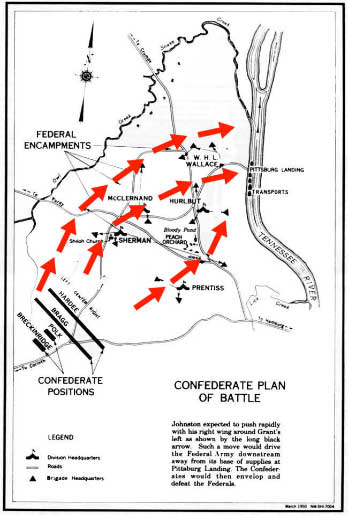

But, allow me to play armchair General, oh goodie! Johnston’s phalanx battle plan (which I pointed out here) was probably where the problems started and was the main reason for the confusion among his fighting units. However, it could still have been used had he created an anvil and hammer strategy like we have seen, though not successfully, at Stone’s River and other places. See map below for original Confederate battle plan:

Instead of trying to push Grant away from Pittsburg Landing, Johnston should have made it the anvil, and came crashing down on it hitting Grant’s right (Sherman’s Division). Now what could have been lucky for Jonhston, is that Sherman’s division was almost entirely green. Few had seen combat and some regiments were only weeks into their service. Sherman was also short a brigade that was placed over near the landing. When the fighting started regiments melted away and fled. Sherman’s division was reduced to nothing in a matter of hours against one division from the Confederates.Additionally, the landing would not have provided much of an escape. It would have taken hours and hours for Grant to evacuate in case of a disaster. Had Johnston been able to achieve the crushing blow he wanted, he would have indeed forced Grant’s capitulation.

Grant’s best route for escape would have been the Hamburg-Savannah River Road, which lead to Crump’s Landing. By hitting Sherman’s position hard with Hardee and Polk’s divisions, Johnston would have collapsed the inexperienced and nervous brigade, thrown it back into McClernand’s division, which would have been catastrophic. Then the Confederates could wheel and turn the flank and force the Federals back up against the river with no real escape. See map below (with my adjustments):

While Hardee and Polk collapsed Sherman, Bragg and Breckenridge would essentially follow the same route and push Prentiss and Wallace back towards the landing where Grant’s entire army would be compressed without an escape route. The mass of humanity collapsing onto the landing would have made any defense and escape impossible.The hammer would have crushed Grant’s army upon the anvil (the Tennessee River).

Whew, that was fun. Anyone care to interject and correct me or make suggestions?

John S. Phelps (pictured left) was a lawyer and a Democrat Missouri congressman. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, he enlisted as a private in the Missouri Infantry. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on October 2, 1861 and to colonel December 19, 1861. By special arrangement with President Lincoln, Phelps organized an infantry regiment which bore his name, Phelps’s Regiment, Missouri Volunteer Infantry. The regiment spent most of the winter of 1861—62 as the garrison of Fort Wyman at Rolla. In March 1862, Phelps led his regiment in the fierce fighting at Pea Ridge in Arkansas. He was mustered out May 13, 1862. In July 1862, he was appointed by President Lincoln as Military Governor of Arkansas.

John S. Phelps (pictured left) was a lawyer and a Democrat Missouri congressman. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, he enlisted as a private in the Missouri Infantry. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on October 2, 1861 and to colonel December 19, 1861. By special arrangement with President Lincoln, Phelps organized an infantry regiment which bore his name, Phelps’s Regiment, Missouri Volunteer Infantry. The regiment spent most of the winter of 1861—62 as the garrison of Fort Wyman at Rolla. In March 1862, Phelps led his regiment in the fierce fighting at Pea Ridge in Arkansas. He was mustered out May 13, 1862. In July 1862, he was appointed by President Lincoln as Military Governor of Arkansas. He is of course referring to Curtis’s Army of the Southwest. As you will see, Phelps is suggesting that Curtis kept his army near cotton rich areas for the sole purpose of cotton speculation. Entire brigades would be sent out on cotton stealing and confiscating missions that would cost the lives of many soldiers. The cotton speculating trickled down all the way to colonels and surgeons.

He is of course referring to Curtis’s Army of the Southwest. As you will see, Phelps is suggesting that Curtis kept his army near cotton rich areas for the sole purpose of cotton speculation. Entire brigades would be sent out on cotton stealing and confiscating missions that would cost the lives of many soldiers. The cotton speculating trickled down all the way to colonels and surgeons.