[I wanted to extend this to 5 parts but I am on my way out of town, so here is a big final part. This was a paper I submitted during my masters program.]

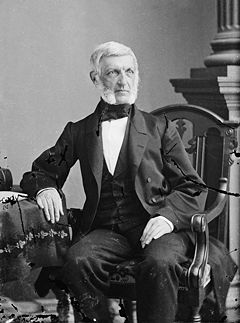

Henry Adams was a descendant of the iconic Adams family of presidents and statesmen, and while making his journey into the historical profession was more natural than most, he desperately wanted to be a politician but failed. Adams greatly influenced future noted historian Carl Becker. Though the scientific method was radically changing historical methodology, the idea of progress was still not far away for Becker and others as he “had postulated history as the record of progress” for society. But unlike Jackson and Bancroft, this all changed for Becker as he discovered a new kind of “complexity” in history and the evolution of the historical record. The impact was so decisive that he literally went back and rewrote previous works. Adams was one of the first to train his students in the “meticulous critical methods of German scholarship.” American students were encouraged to study abroad and upon returning to America they in turn instructed future students in the German school of scientific inquiry.

Henry Adams was a descendant of the iconic Adams family of presidents and statesmen, and while making his journey into the historical profession was more natural than most, he desperately wanted to be a politician but failed. Adams greatly influenced future noted historian Carl Becker. Though the scientific method was radically changing historical methodology, the idea of progress was still not far away for Becker and others as he “had postulated history as the record of progress” for society. But unlike Jackson and Bancroft, this all changed for Becker as he discovered a new kind of “complexity” in history and the evolution of the historical record. The impact was so decisive that he literally went back and rewrote previous works. Adams was one of the first to train his students in the “meticulous critical methods of German scholarship.” American students were encouraged to study abroad and upon returning to America they in turn instructed future students in the German school of scientific inquiry.

Adam’s generation of historians followed the lead of noted German historian Leopold von Ranke, who is considered to be the “pioneer” of the scientific school of historical scholarship. This time period was the turning point in the American historical profession. It is at this time when the idea of “objectivity” comes to the forefront. As noted, Adams was one of the first to train his students in the scientific method, but he still believed in “American Exceptionalism” and that “the average American” was wiser and better off than his European counterpart. Adams saw the study of American history as a “laboratory in which one could study undisturbed the social evolution of democracy.” Though his methods were more objective than any previous generation of American historians could have hoped for, Adams still saw American greatness and progress and that American history was the most worthy of study as it “represented the greatest democratic evolution the world could know.”

Though the idea of American progress was still present in the writings of these new “scientific” historians, there was something very different about their philosophy. The economic interpretation of history as seen in the writing of Karl Marx was making an impact. As Adams himself admitted in his autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams, “he [Adams] should have also been a Marxist,” if it were not for his New England sensibilities and aversions to socialism. But there was something about the notion of history as a constant struggle between classes that appealed to him at one time in his career. Adams was not immune to seeing “phases” in history that centered on economic and social struggles, and he was not alone. Why was this becoming prominent in many academic circles? The advent of the Industrial Age, the growth of enormous cities and along with it the distribution of wealth and the growing gap between rich and poor. A new movement was taking hold in the American historical profession and one that had its roots in the social conditions of the era.

As Robert H. Wiebe noted in his “The Search for Order: 1877-1920″ the late 19th Century was one of great change that left many Americans searching for a sense of normalcy that had been lost in the transformation to a modern industrial society. This led many to a movement that would become known as Progressivism and the Progressive Era – the most important and influential political and social movement of the time and perhaps in all of American history.

It wasn’t just a social and political movement, it was a cultural shift. Just as Bancroft was a child of Victorian American, so too were the scholars of early1900s who were born from the progressive womb. These early Progressives were vital in moving the American historical profession to a truly scientific and professional level. They challenged the status quo and dared to present thesis’s that were controversial.

In 1919 Harry Elmer Barnes published History, its rise and development: a survey of the progress of historical writing from its origins to the present day, and in it he outlined the progress of the American historical profession: “The application of the more critical methods to the field of American history has resulted in works worthy to rank with the best European products and has quite reconstructed the earlier notions of American national development.” Barnes evaluated the evolution of the profession starting with Bancroft and his post-Civil War work to the current Progressives and saw that “the new scholarship had permeated the whole American university world” and was creating students who applied their methods to historical investigation. And just as importantly, the interpretation of American history had “finally been secularized.” The progress that these new historians believed in was not that of Bancroft’s theological and patriotic (American Exceptionalism) discourse, but of a progress in institutions and not men alone.

As the United States became an industrial power and the social injustices of poverty, distribution of wealth, worker’s rights, and women suffrage became important battle cries of Progressives, the historian was at work attempting to explain and interpret the present state of affairs and of historical progress. American scholars once again joined with their European counterparts and determined (echoing Marx) that an economic determination of events seemed to be at play. And they were correct; there had not been any serious inquiry into the economic aspects of historical events. There was a void and it was going to be filled.

The scholars from 1900-1920, especially, noted one historian, were looking for “economic determents” in their quest for an economic “synthesis of society.” They wanted, as did Bancroft, a usable past that for them could help address current social ills. There were studies that looked critically, for the first time in American history, at capitalism and the motivations of corporations and the evils of monopolies. Progress was not just wealth, but poverty. One of the first to look critically at economics was Edwin R.A. Seligman who wrote The Economic Interpretation of History in 1902. Not far behind was Gustavus Myers’ The History of the Great American Fortunes (1907). Algie M. Simmons, a committed socialist, wrote openly about the Social Forces in American History (1911) that first circulated as a pamphlet and addressed social ills as symptoms of economic injustices. There were histories about the “Robber Barons” and “Captains of Industry,” and each time economic synthesis was the goal.

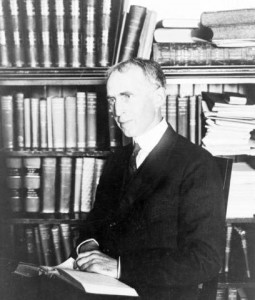

There are two solid candidates for our “best” representation of the era: James Harvey Robinson and Charles A. Beard. Robinson was openly critical of the previous schools of historical investigation and rightly so. To Robinson the work of Bancroft was a “crime” against history. But though Robinson was eloquent and forceful (he was a champion of “value-free” objectivity), the best representative of the time period is Beard.

Beard’s first book, The Industrial Revolution (1901), was essentially an economic interpretation of history and in it he proclaimed that the Industrial Revolution was the “universal driving force” of history, not some vague “exceptionalism” or cultural advancement. But Beard’s most important book is perhaps the most controversial American historical study ever written: An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution. This work best represents the Progressive sensibility of progress in the American historical profession of the time. The book shocked contemporaries and as historian Ernst Breisach noted, it should not have. All of Beard’s work was an examination of phases and processes in American history and at the core of it were always economic determinants.

Beard’s first book, The Industrial Revolution (1901), was essentially an economic interpretation of history and in it he proclaimed that the Industrial Revolution was the “universal driving force” of history, not some vague “exceptionalism” or cultural advancement. But Beard’s most important book is perhaps the most controversial American historical study ever written: An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution. This work best represents the Progressive sensibility of progress in the American historical profession of the time. The book shocked contemporaries and as historian Ernst Breisach noted, it should not have. All of Beard’s work was an examination of phases and processes in American history and at the core of it were always economic determinants.

An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution caused an uproar, but not within Progressive academia. Newspaper editorials howled and the Right was up in arms over the abomination of Beard’s analysis, which, to put it simply, was not about American Exceptionalism and progress, but greed and power. The Founders were simply looking out for their own economic interests first, Beard concluded. He openly challenged Bancroft and his “mystic” reverence for the Founders and the Constitution. He also challenged the “so-called” scientific and objective scholars who had failed to come to his same conclusion.

Beard was, frankly, blazing a trail few dared to burn. As for his idea of “progress,” he was explicit:

The whole theory of the economic interpretation of history rests upon the concept that social progress in general is the result of contending interests in society – some favorable, others opposed to change.

Beard wanted to rescue American History from mythology at best and mysticism at worst. He used strong language such as “economic determinism” and would be accused of being a socialist. Was Beard influenced by Marxist ideology, of course, but as historian Peter Novick attests, Beard outright “rejected” Marxism. Beard bemoaned the interpretation of the Constitutional Convention as a “popular product” and created by impartial and disinterested men. Beard years after publication claimed that he did not go in search for what he found and that when he found the economic motivations behind the Founders it was, “the shock of my life.” Others have since argued that Beard was a Marxist and his goal was to destroy the image of the Constitution as a sacred document and put in its place the concepts of class struggle and Marxist ideology. The Constitutional Convention enhanced the few at the expense of the many and established the ultimate Bourgeois state, according to a Marxist interpretation.

Beard wrote that “the devotion to deductions from principles exemplified in particular cases, which is such a sign of American legal thinking, has the same effect upon correct analysis which the adherence to abstract terms had upon the advancement of learning.” For Beard it was about taking the Founders and the Constitution off the mantle and to consider them as men and not demigods. As modern scholar and American Revolution historian Gordon S. Wood has noted, that though Beard has “been proved wrong on almost every count,” he was “right” in his desire to remove the “mythical” nature and reverence of historical scholarship concerning the Founding that had taken place up to that time.

By 1914 historians were amazed at how far the American historical profession had come in its quest for objectivity and professionalism. The “New Historians” were filled with optimism and compared their craft with that of the great German historians. Jameson had declared at one time the work of American historians as “second class,” but was now sure that “an age of generalization, of synthesis, of history more largely governed and informed by general ideas” was now possible. Though an exaggeration to be sure, Jameson had reason for optimism for as we have seen the development of the American historical profession had been transformed by the early 1900s into something resembling modern historical scholarship.

There is little doubt that Bancroft would have been appalled of Beard’s economic interpretation of the American Constitution. Beard was equally critical of former generations of historians who failed, in his mind, to ask the tough questions. Both men had clear ideas of progress and the historical profession and how best to analyze and present historical data. For Bancroft the founding of the nation and the successful conclusion of the Civil War was proof that God’s will had been achieved and that America had faced its last great test. The country had finally fulfilled its promise of freedom and had become an empire of liberty. The values of the Founders had been justified and validated. There was in his eyes no need for a continuation of progress and as already noted, he even hinted at the end of history (progress) for America.

By 1920 the Progressives had experienced what they felt was the singular great challenge for America in the form of economic injustice and political corruption. Industrialization had created a “search for order” and an economic interpretation of history fit the needs of the Progressives just as Bancroft’s theological patriotism did Victorian America. The focus on progress of American institutions and government aided the Progressive causes as they sought to improve working conditions, poverty, immigration and suffrage rights. The economic interpretation of Beard made more sense to this generation than did the writing of proceeding generations. As we have seen, each new generation from 1870 to 1920 was flawed and some more deeply than others, but all sought what they believed was a usable past that conformed to the needs of their generation to strengthen their values and assumptions. By 1920 the scientific revolution ensured that the American historical profession would use methodological approaches to eventually ensure as much historical accuracy and objectivity as possible.

Peter Novick wrote in the Introduction of his book, The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession, that he hoped to look effectively into what historians “thought” they were doing and what they thought they “ought” to be doing as they created history. He wished to encourage historians to a “greater self-consciousness about the nature” of their work. Novick succeed brilliantly and in this short presentation, I think, we have examined how the role of “progress” in historical interpretation and understanding, at the very least, informed if not encouraged the advancement of the historical profession.

I thought we were in a “Great Recession”? Well somebody please tell California that. The state that is cash poor and literally broke has unveiled a $578 million K-12 super complex that will handle 4,200. This is a shocking example of a recent trend in what are being called “Taj Mahal” schools costing $100 million-plus that are already built or being built. Call me crazy, but people in California are nuts. This school cost more than the China Olympic Stadium they built a few years ago. C’mon! At a time when teachers are losing jobs, states are writing IOU’s, and government spending is out of control, do we need mega high schools?

I thought we were in a “Great Recession”? Well somebody please tell California that. The state that is cash poor and literally broke has unveiled a $578 million K-12 super complex that will handle 4,200. This is a shocking example of a recent trend in what are being called “Taj Mahal” schools costing $100 million-plus that are already built or being built. Call me crazy, but people in California are nuts. This school cost more than the China Olympic Stadium they built a few years ago. C’mon! At a time when teachers are losing jobs, states are writing IOU’s, and government spending is out of control, do we need mega high schools?